The A.I. Monarch

Scattered thoughts on the human faculty of discernment as an ineradicable aspect of creativity

I.

Back when I was a little kid, I used to play a game called Microsoft 3D Movie Maker. It was this crappy little program that came with our Windows 95 family computer, and it was marketed to nine-year-old children as a way of making your own cartoons using some pre-made 3D polygon models against various pre-made digitally-painted static backgrounds (with a selection of different camera angles). If not for the internet, the game would have been pretty worthless — just a distraction to help you kill a few hours before you discard it and find some other, more competently programmed game to play. But as luck would have it, a collection of mentally ill teenagers decided to keep playing the game years after it was released and submitted their movies online. They wound up creating a forum and started challenging each other to make better and better movies, eventually stretching the program’s possibilities far beyond what the developers had intended, even at the paltry framerate of 6.6 per second (see here for an example of what the program’s movies were supposed to be like, and here for an example of what teenagers did with it).

I bring this up because 3D Movie Maker had something called The Ideas Room, which was designed to give its prepubescent users some inspiration regarding what kind of movie they ought to make. Here is the game’s mascot, McZee, giving us a tour of this room:

So in this Ideas Room, there was a device called the “splot machine.” The concept was, you’d click the machine, and it would take you to a screen showing a possible shot from a movie. On the right, there’d be a button that resembled a slot machine crank, and if you clicked that, then the game would “brainstorm” something for you by giving you three things: a random background, a random “actor” (which was just one of 40 available polygon models of people), and a random “prop,” all strewn together at once. There were precious few props, by the way: just a couple cars whose colors couldn’t be changed, a camping tent, a safe, a rocket, a totem pole, a hot-air balloon, a cylinder, a cube, a sphere, and a few other baffling objects — nothing you’d actually want, like a gun, or a book, plants, furniture, or anything you’d typically see in a movie. Thankfully, the game allowed users to use 3D letters as props, so we’d type in the letter “L” and turn it sideways, making for a pretty good ersatz gun.

Now, about 99% of the time, if you were to use the “splot machine” you’d get absolutely nothing of any value whatsoever. You’d click the button, you’d get nonsense. You’d get something like, a black boxer in his red boxing trunks standing in the middle of a cave next to a pink cube partially going through his head. Worthless. So you’d click the button again, and you’d get more nonsense. You wouldn’t get anything that could possibly form the chrysalis of a coherent idea… except maybe after a hundred tries, and then you’d get a character who at least looks like he belongs in the setting with a prop nearby that seems logical. But by that point, you’d realize that the whole activity has a weak return on investment, and so you’d go make your movie, trying your best to creatively reassess what the props and actors can be used for.

It occurred to me the other day that the “splot machine” was a primitive version of the way creative people now use AI software for art. I have some very idealistic friends who deny that any artist would ever use AI, because supposedly a true artist would see this technology as beneath him… but from what I’ve been seeing, artists are among the most interested in experimenting with this new technology, and they want to stretch its capabilities beyond what people consider possible. This is how artists always are. But from what I’ve gathered, AI-generating a good background, or evocative image, or useful piece of music involves an insane amount of trial-and-error. You click the retooled AI “splot machine” button, it gives you garbage, and so you try it again. And again. And again. And then you get something where some tiny aspect of what you’ve generated might come in handy, so you save that, and then you try it again. And again. And so on. The “AI” is “creating” the content by combining previous data, sure, but it’s really the discernment of the individual — endlessly generating new ideas, trying out new prompts, and then assembling and curating the results — that creates the art. The art is produced via negativa. You get the machine to give you a mountain of dung as you comb through it, trying to find perhaps some morsel of gold.

Taken in a certain sense, the way people are working with AI to create art resembles the manuports of prehistoric man. A manuport is a natural object that someone spotted in nature, picked up, moved, and kept without any further modifications, typically stored among a hoard of other, more useful things. Manuports may have been the first art ever created, even though no manipulation of any materials ever occurred. It’s the eye that creates the art, and it creates entirely through interpretation and judgment.

II.

Now, let me pose this question. Given what I’ve said above, who do you think can AI replicate more successfully? The “artist,” or the art-picker? The art-chooser? In a sense, this is a trick question. The artist, who plays the role of a craftsman and artisan for our purposes, is always the art picker because he’s constantly criticizing himself, correcting himself, and reassessing what he’s doing every step of the way (I’m not including the people who just pay guys to sculpt or paint their ideas). The artist is a tinkerer by nature. But when you split the act of generation from the act of assessment, we see clearly that the AI can replicate the generator better than the assessor. Only the art picker will have the great ingenuity required to recognize the exigencies of the historical moment, the semiotic weight that a work can carry, the manner in which a piece might interact with the social and cultural environment that both surrounds it and came before it. This principle is partly why abstract expressionism grew so big during the 20th century — in an increasingly saturated media environment, people understood that the critics are themselves in a sense creating the art by tempering expectations and providing the interpretant in the minds of its viewers and admirers. Northrop Frye recognized that the critic may one day replace the artist.

So this question got me thinking. Does the same principle apply to politics? Let’s say hypothetically you have a “king” and a king-picker — what’s easier to artificially replicate? It’s hard to avoid concluding that the same principle as with art applies to politics as well, particularly as society becomes more complex. There was a revolution in mass and scale that occurred around the turn of the twentieth century, and bureaucracies concomitantly took on a far bigger role in political life. The government is no longer ruled by a king, since all the calculations that the guy occupying the top position needs to make are far too vast to do by himself. Instead, you’ve got various teams of advisors, lobbyists, and bureaucrats all trying to propose things that would take up his time in office and become part of his political legacy. But if there were a king ruling over a country with any level of modern complexity, I doubt he’d really need any more ingenuity than a president, either. He certainly wouldn’t need imagination. He would simply follow the prompts he’s fed and combine them in various ways, to do various things. I believe that you can indeed create an AI monarch, but I’m not convinced that you can create the person, or body of people, who will assess his actions and deem them worthy.

Back in the late 00s, the blogger Mencius Moldbug AKA Curtis Yarvin was trying to deal with all of these questions. He’s a man who wants to bring sovereignty back to politics, and, as Carl Schmitt observed, the sovereign is he who forms the exception. The sovereign is allowed to be spontaneous — he’s no robot! So Moldbug created his system called “Patchwork.” The underlying premise here is that all states are structurally the same thing as corporations, right down to their main purpose, namely to accumulate and sit on vast amounts of capital. The monarch accordingly is the same essential thing as the CEO of the Apple corporation. So, Moldbug reasons, why keep the illusion alive that they are any different? Why not restore monarchy with its thousands of years of success by fully privatizing nation states and turning them into joint-stock sovereign corporations, or “SovCorps”? That way, the world can become a patchwork of little SovCorp city-states who all respect each other’s sovereignty, just as intended with the system of international law that came out of the peace of Westphalia. And if citizens want to leave one SovCorp, why, they can just switch to a different SovCorp, the way consumers switch brands!

I don’t believe Mencius Moldbug is a particularly good political philosopher, but there’s something sort of ingenious to this rather simple idea, mainly because it takes the reasoning of libertarianism and pushes it so far that it implodes the whole political concept. Instead of being concerned about “big government,” the cosmopolitan techno-commercialist Yarvinite decides that the secret is making the corporation so big that it becomes its own little government. So how does this arrangement work? Well, Moldbug explains:

Obviously, a joint-stock realm faces completely different problems in maintaining internal security. Internal security can be defined as the protection of the shareholders’ property against all internal threats — including both residents and employees, up to and certainly including the chief executive. If the shareholders cannot dismiss the CEO of the realm by voting according to proper corporate procedures, a total security failure has occurred.

The standard Patchwork remedy for this problem is the cryptographic chain of command. Ultimately, power over the realm truly rests with the shareholders, because they use a secret sharing or similar cryptographic algorithm to maintain control over its root keys. Authority is then delegated to the board (if any), the CEO and other officers, and thence down into the military or other security forces. At the leaves of the tree are computerized weapons, which will not fire without cryptographic authorization.

[…]

For our overall realm design, let’s simplify the Anglo-American corporate model slightly. We’ll have direct shareholder sovereignty, with no board of directors. The board layer strikes me as a bit of an anachronism, and it is certainly one place stuff can go wrong. Deleted. And I also dislike the term ‘CEO,’ which seems a bit vainglorious for a sovereign organization. A softer word with a pleasant Quaker feel is delegate, although we will compromise on a capital. And we can call the logical holder of each share its proprietor.

[…]

This fragile-looking design can succeed at the sovereign layer because, and only because, modern encryption technology makes it feasible. The proprietors use a secret-sharing scheme to control a root key that must regularly reauthorize the Delegate, and thus in turn the command hierarchy of the security forces, in a pyramid leading down to cryptographic locks on individual weapons. If the Delegate turns on the proprietors, they may have to wait a day to authorize the replacement, and another day or two before the new Delegate can organize the forces needed to have her predecessor captured and shot. Fiduciary responsibility has its price.

Thinking about the idea of an artificially intelligent king reminded me of this essay, because the way Yarvin describes the relationship between the shareholders/proprieters and the CEO/Delegate is exactly the relationship between the person pulling the lever on the “splot machine,” or generating images from the same prompt using AI software over and over. Typically with real corporations, it’s the Board of Directors who appoint a CEO, and the shareholders who appoint a Board of Directors. But here we don’t have a Board of Directors, and without one, I can’t see how you wouldn’t get shareholders firing CEOs pretty regularly. Using your cryptographic blockchain technology, you simply keep getting rid of monarchs you don’t like until you get the one who seems OK. Is that monarch really in control of anything?

Now, I have no idea if Yarvin still endorses this exact model, as I haven’t read any updates on it for years. I’ve seen some criticisms floating around lately that he doesn’t really care about the “SovCorp” idea so much anymore, and he’s now more into endorsing the basic concept of having a king rule everything without going into specifics. But in this early, perhaps rougher-hewn version of his thought, there was a specific plan, and it prompts the question as to how much agency a modern monarch, even in this system specifically designed to restore his sovereignty, truly has. We also don’t ever get a sense of how the monarch, CEO, or Delegate is chosen. Do the shareholders simply elect him anonymously using their cryptographic blockchain technology? What is the nominating process? In a way, I suspect that Yarvin really did have something like a digital robot king in mind. He wasn’t thinking of warm bodies; he was thinking of structures. And when you really give it some consideration, the warm body of the monarch has always been a hindrance to good governance, since the “body politic” that he represents is an altogether different entity, as even the medievals understood (see Kantorowicz on this point).

Here’s another question. Or questions. What position within a government is easier to program if you’re trying to build yourself a robot? An AI treasurer, or an AI king? An AI military general, or an AI king? An AI postmaster, or an AI king? I’d say it’s the latter in all three cases, and I’d even add that it’s easier to program an AI king than the AI town dog catcher. “Kings” are easy. Complex decision-making all takes place within the realm of discourse, i.e. symbolic communication, and if AI knows anything, it knows how to do that. Relatively simple managerial work, on the other hand, is far harder to replicate. There’s nothing simple about programming the ability to balance the exigencies of the moment and exercise the critical faculty of judgment. A robot king can simply propose ideas based on the options he’s presented by various advisors, and the shareholders/Proprietors can always decide to give him the shit-can. And with a robot king, you don’t have to deal with any nominating process — you can just simply pull the “splot machine” lever.

III.

Good ol’ Cowboy Curtis couldn’t have possibly escaped this problem of sovereignty and human agency with his brand of techno-commercialism (he calls it “neocameralism”). And in any case, he shot himself in the foot because his commitment to the truth was too strong. He could have taken a de-fanged version of his idea, trotted it around to various bigwigs and tech journalists, and presented it as a wacky new development within a mostly safe and inoffensive libertarian discourse. Everything would have gone swimmingly. He could have gotten the entire Reddit forum on his side. But instead, he went on and on, talking about the possibility of natural masters and slaves, race and intelligence, Thomas Carlyle’s most shocking works, and other unwholesome topics and scary subjects. This is why we appreciate Yarvin, perhaps against our better judgment.

But the mechanistic conception of the state, even in doctrines putatively about authoritarianism and individual rule, has been around for quite some time. The first mechanistic thinker was Hobbes. Carl Schmitt, in his mid-career monograph The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes (1938), explains that although it’s the sovereign who’s meant to rule over the state, the state itself has been so thoroughly mechanized that the sovereign merely forms a seal on what’s essentially an autopoeic entity:

The sovereign-representative person cannot thus delay the complete mechanization of the state. It is only a timebound expression of the baroque idea of representation of the seventeenth century, of absolutism, not of a “totalism.” Because the state in Hobbes’ theory is not a total person—because its sovereign-representative person is only the soul of the “huge man” state—the process of mechanization by means of this personification is not only not delayed but actually completed. This personalistic element is drawn into the mechanization process and becomes absorbed by it. As a totality, the state is body and soul, a homo artificialis, and, as such, a machine. It is a man-made product. Its material and maker, materia and artifex, machine and engineer are one and the same, namely men. Also the soul thereby becomes a mere component of a machine artificially manufactured by men. The end result is therefore not a “huge man,” but a “huge machine,” a gigantic mechanism whose function is to protect the physical existence of men whom it rules and guards.

Neither the drape in the foreground that shows a fantastic picture of the leviathan nor the contemporaneous animation expressed by the sovereign-representative person can change the fact that because of Hobbes, the state became a huge machine.

[…]

The decisive metaphysical step in the construction of the theory of the state occurred with the conception of the state as a mechanism. All that followed—as, for example, the development from the clock mechanism to the steam engine, to the electric motor, to chemical or to biological processes—resulted in the further development of technology and scientific thinking, which did not need any new metaphysical determination. Through the mechanization of the “huge man,” the μακρός ἄνθρωπος, Hobbes leapt decisively ahead of Descartes and made a significant anthropological interpretation of man.

It is in Hobbes that we find a purely individualistic, atomized conception of man, and yet men come together collectively to form the massive state due to their shared, universal fear of nature’s wrath. Though Hobbes ultimately wanted human agency to be preserved in the form of the sovereign, the very process through which he’s appointed precludes the possibility of the sovereign acting as anything other than a machine, itself governing a machine. Given Hobbes’s anthropological views, there’s no way this problem could have been avoided. Anything truly “human” in the sovereign’s rule would have to be judged as an error.

Yarvin’s idea winds up with a similar but different problem, and one more apropos of our time. While he doesn’t share Hobbes’s anthropology, which means that there’s still a human element at play, all the humanity lies in the opposite party intended. The shareholders truly are the seat of power, and being the seat of power, they’re also the seat of creativity. This is because even in political decision-making, or art, the ability to discard something means the ability to manipulate the genus to which it belongs — to treat it as raw material. The faculty of judgment is the source of political creativity, here, not the ability to come up with ideas and execute them — just as the same faculty is the more creative power in both AI generation and manuport collecting.

When we talk about great innovators in the fields of business, politics, and art, we say that they possessed “the vision” needed to make things work. This is an even greater metaphor than perhaps we realize. The eye’s main job is to take in its surroundings, observing carefully and with particularity what’s presented to it. What it sees as important or significant is something borne of intentionality, a mysterious process that I don’t believe we’ll ever be able to digitally replicate — at least not along the lines of man’s animal nature, the very thing that all of his tools are there to serve. Additionally, at least according to Plato, the eye is not really passive. It is quite active insofar as it sends forth an occult flame originating in the soul to retrieve the image, a poetic truth whose profundity we’re only now finding ourselves able to appreciate once more. Our tools and innovations ultimately benefit the eye, allowing it to do its job unencumbered by the need for the rest of the body’s labor.

But at a certain point, it’s worth asking what becomes of man’s endeavors when everything he does is reduced to the eye.

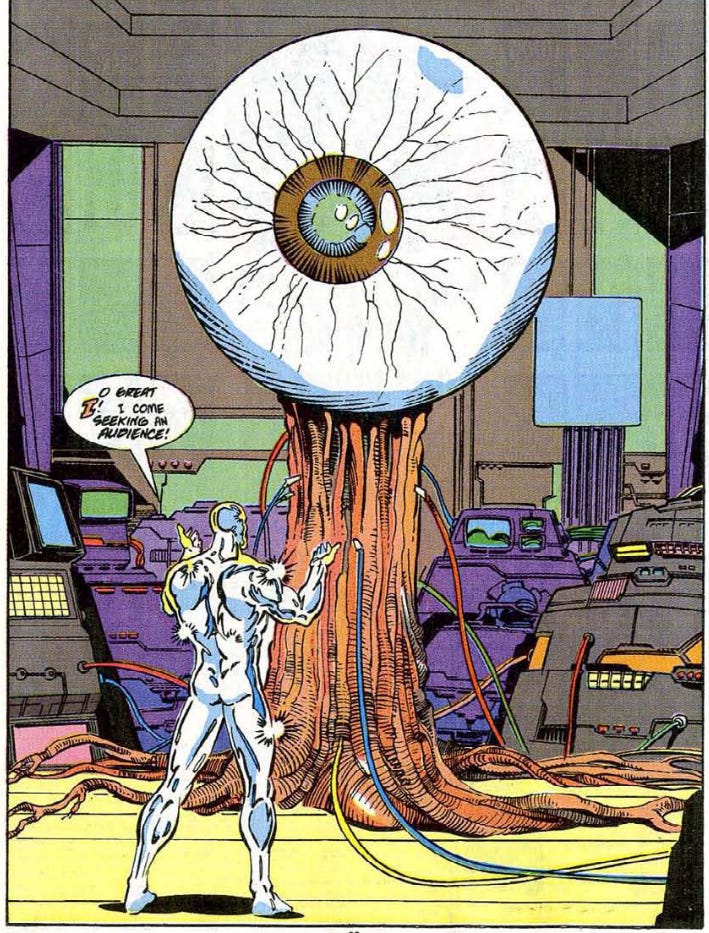

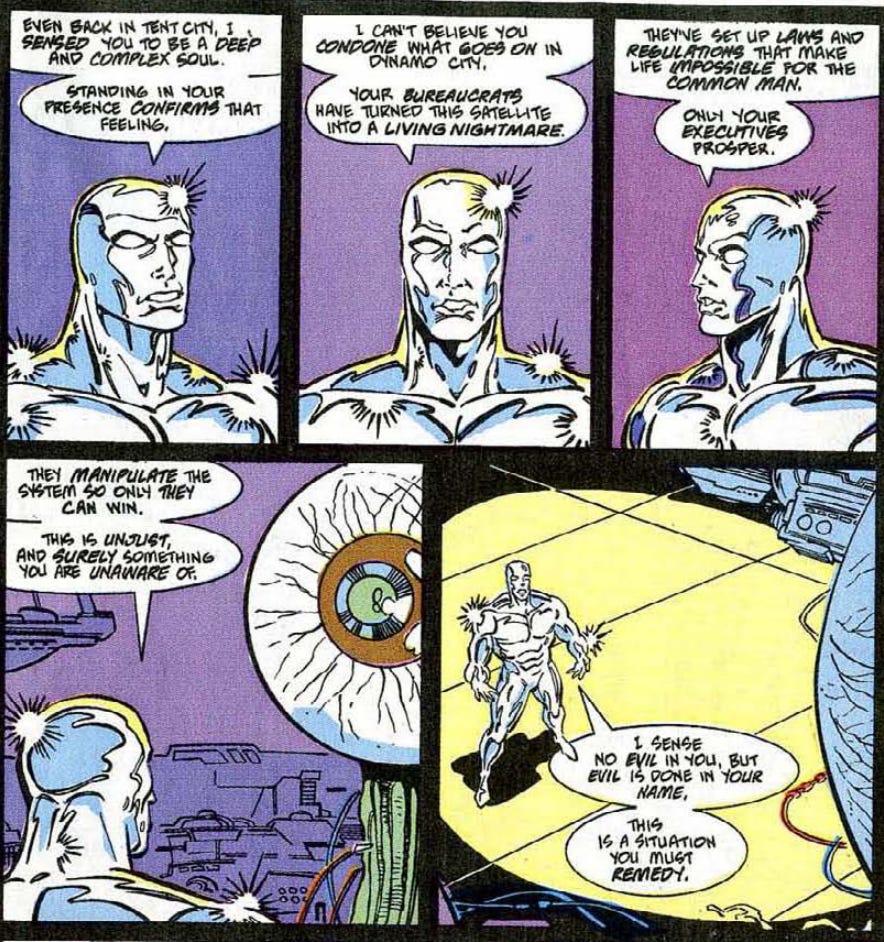

By the way, there was a story arc in Silver Surfer comics in which the hero visited a technologically advanced city-state led by a monarch who was also its CEO. Did you know that? It’s quite a yarn! Here, just for fun (and moreover not being one who knows how to write a good conclusion), I’ll let the climax of that story have the last word.

Edit: 10/11/2024 - made a couple quick corrections and edits for clarity