Competitive Debate and The Decay of Dialogue, part 1

Assessing the main problems concerning American competitive debate (in high school and college)

I. The Video

In 2014, a little over ten years ago, a video went viral that exposed the hollow nature of collegiate-level debate. In it, two young women from Towson University, Korey Johnson and Ameena Ruffin, are shown on the news discussing their win of the 2014 annual Cross-Examination Debate Association (CEDA) national championship. It all seems quite legitimate, at least at first. Ameena is asked what the debate subject was, and she says, almost sheepishly, “Um, the topic was restricting presidential war powers authority…” But then, just as the viewer has been lulled into believing that a tasteful war of wits between two teams of young scholars is all that transpired, we are abruptly shown some spliced-in footage of how they actually look when they’re debating. And this is clearly material that the news segment would never have intended the viewers to see:

In a word, they look ridiculous.

I’ll quote the first segment of Ameena Ruffin debating here, transcribing it as best I can, with the most charitable punctuation that I can think to insert:

They say the nigga’s always already queer. That’s exactly the point. It means that the impact [garbled] that is an impact term… uh, to the affir… uh, that is the case turn to the affirmative because we, uh, we are saying that queer bodies are not able to survive. This necessarily [?] means the body, uh, the nigga, uh, is not able to survive…

And then the sentence cuts off. This may have been the best transcription I could do, but it simply isn’t enough to read what they’re saying. You must watch the video — the whole entire thing — because the performance is quite the sight to see. The speakers are attempting to talk extremely quickly, often flailing their arms about as they speak, and their “uhhs” resemble something halfway between filler words (the kind that middle-school teachers discourage their students from using) and desperate gasps for air that you’d expect to hear from someone suffering from a panic attack.

On and on the video goes, cutting back and forth between the debaters on the news looking serious and professional, and the same debaters in the actual debate, sounding absolutely deranged. Here is a transcription of another quick segment, this time featuring Korey Johnson, also with some charitably-placed punctuation:

So th-th-the way the status quo works is through, uh, whiteness allowing, uh, forcing other bodies to tell, uh, narrations [?] of whiteness and, uh, the violences [sic] that whiteness does. We, uh, say that that is the length that we will go for…

…and then the video cuts back to them in the news segment, right as Korey was reaching the riveting conclusion of her well-informed sentence. Their opponents, to their credit, didn’t bother with all the fast-talking stuff. They just decided to put on a “conscious” rap performance about being black instead.

Just to be clear, Ameena wasn’t lying. The debate topic really was about presidential war powers. According to the CEDA web site, the full resolution up for debate was:

The United States Federal Government should substantially increase statutory and/or judicial restrictions on the war powers authority of the President of the United States in one or more of the following areas: targeted killing; indefinite detention; offensive cyber operations; or introducing United States Armed Forces into hostilities.

So what exactly happened there? How did this reasonable policy proposal lead to… whatever that was?

Well, fortunately, our friends at The Atlantic not only covered the event, but covered it with unrestrained enthusiasm in a piece entitled “Hacking Traditional College Debate's White-Privilege Problem.” Here’s what this article had to say (emphasis mine):

It used to be that if you went to a college-level debate tournament, the students you’d see would be bookish future lawyers from elite universities, most of them white. In matching navy blazers, they’d recite academic arguments for and against various government policies. It was tame, predictable, and, frankly, boring.

No more.

These days, an increasingly diverse group of participants has transformed debate competitions, mounting challenges to traditional form and content by incorporating personal experience, performance, and radical politics. These “alternative-style” debaters have achieved success, too, taking top honors at national collegiate tournaments over the past few years.

[…]

On March 24, 2014 at the Cross Examination Debate Association (CEDA) Championships at Indiana University, two Towson University students, Ameena Ruffin and Korey Johnson, became the first African-American women to win a national college debate tournament, for which the resolution asked whether the U.S. president’s war powers should be restricted. Rather than address the resolution straight on, Ruffin and Johnson, along with other teams of African-Americans, attacked its premise. The more pressing issue, they argued, is how the U.S. government is at war with poor black communities.

In the final round, Ruffin and Johnson squared off against Rashid Campbell and George Lee from the University of Oklahoma, two highly accomplished African-American debaters with distinctive dreadlocks and dashikis. Over four hours, the two teams engaged in a heated discussion of concepts like “nigga authenticity” and performed hip-hop and spoken-word poetry in the traditional timed format. At one point during Lee’s rebuttal, the clock ran out but he refused to yield the floor. “Fuck the time!” he yelled.

So stunning. So brave. And CEDA, I want to clarify, is not some rinky-dink nonsense debate organization. It is considered one of the highest that college-level debate has to offer.

II. Tactic #1 - Kritik

For most of its viewers, this viral video exposed the vacuity of something that they had not even thought much about since their teenage years. Competitive debate is a common activity that ambitious high school students use to pad their college applications, hoping to look good for prestigious universities. But the majority of students don’t participate in it. When most people think “debate,” they think of arguments meant to sound convincing to reasonably intelligent people within the broader citizenry. They’re thinking of the debates that occurred in that movie The Great Debaters (2007), in which the debaters talk real slow and dramatically while tear-jerking Hollywood music plays in the background. Most of the people who watched that video sure weren’t expecting anything like that.

When the video first came out, the conservative columnist Steve Sailer reacted to it, observing a few things (and unfortunately I’m going on memory here, since Ron Unz’s web site doesn’t seem to have archived the post): one was that it’s important to remember that college debate simply doesn’t matter all that much. Debate is used to get into college, and so most students don’t need it anymore once they’re there, unless of course they’re planning to transfer or attend graduate school. His second observation, a corollary to the first, was that college debate cannot possibly be very well-funded. It can’t bring in much money as a spectator event, and thus it probably relies chiefly on donations, sign-up fees from competitors, and other meager contributions. Therefore, it was probably quite easy to corrupt with this sort of absurdity.

I suspect that he was right in saying that debate isn’t a particularly well-funded enterprise, but absurd debates definitely happen at the high school level as well as at college. And the absurdity which most of that video’s viewers found so off-putting can be explained by two tactics that occur regularly within the top debate organizations at both the high school and college level. The first is known as “kritik” or “running theory,” which has been around since the 1980s. A Wikipedia page explains it like so:

In the 1980s, a new argument called a "kritik" was introduced to intercollegiate debate.[24] Kritiks are a unique type of argument that argue "that there is a harm created by the assumption created or used by the other side"—that is, there is some other issue that must be addressed before the topic can be debated.[25]: 19 Early pioneers of the kritik used them primarily as a supplement to other arguments rather than as stand-alone cases.[24] Kritiks faced criticism from traditional debaters and judges because they did not require competitors to directly debate the assigned topic.[24][25]: 24–26 Nevertheless, they took hold and remain a stable [sic] of intercollegiate and high school debate today. Most recently, some debaters have advanced an argumentation style known as "performance debate" which emphasizes "identity, narrative understandings, and confrontation of life's disparities."[23]: 23 This argumentation style, advanced predominantly by Black debaters, has been used by debaters to discuss issues related to identity and difference.[26]

This practice, controversial from the beginning, continues to be criticized from a number of angles. An editorial from 2021 by two experienced high school debate coaches explain its various problems, even giving the reader some interesting examples of ways it has been used (bold emphases mine):

Varsity Public Forum … [i.e.] PF teams have found success running hackneyed “theory,” in which teams try to one-up each other in an unending game of brinkmanship. For those unfamiliar, theory is an argument not about the resolution, but instead about the practices of debaters in round. For example, debaters must disclose their positions on the NSDA PF wiki. Or, an infamous example from Lincoln Douglas Debate – debaters must not wear formal clothing, or, alternatively, shoes.

[…]

[Running “theory”] triggers an inevitable race to the bottom. Barring a wholesale rejection of theory in PF, debaters will be inclined to push the envelope towards less educational shells in blind pursuit of the W. Anyone doubting this devolution need only look as far as font size theory, wherein a team must be dropped for the unpardonable offense of using 11-point font in their case as opposed to 12. The floodgates will open, as they have in LD and Policy, and will steamroll any team that crafts a logical case and brings value to the activity.

The authors additionally make the point that debate coaches have no idea how to assess the validity of a theory that a team attempts to use. They often don’t understand the theories being made, have no idea what they’re reading, and then decide to vote upon them anyway. When I saw responses to the piece in the debate subforum on Reddit, the vast majority disagreed that there is any problem with running theory, insisting that the authors are simply overstating the complexity of arguing theoretically. The top commenter, who received four times as many “likes” as the person who posted the piece, capitalizes the word “Theory,” like so, and insists that even his diaper-wearing children understand Theory, although they don’t know it yet.

I actually believe that there is some merit to that rebuttal. Many of these theoretical arguments aren’t especially brilliant. They, in fact, do seem kinda dumb. And by “dumb,” I mean sloppy, logically slapdash, and loaded with their own set of unstated assumptions of which even the speakers themselves aren’t fully aware. Rather than the supposed complexity of theory, the bigger problem, which none of the most experienced critics of this practice seem to have addressed, is that running theory gives the judges license to vote based on personal prejudices rather than well-established principles. By shifting the topic into unforeseen terrain, judgments can now be made based on only the most superficial criteria, most of which are apparently informed by each individual judge’s vague and under-principled sympathy for the idea of fairness. The tenuous expectations through which a theoretical argument can be judged might, in fact, explain why Towson won the CEDA championship again in 2015, one year after it faced intense online scrutiny, as if the judges just voted to give the finger to everyone who voted for Towson the prior year:

The debate resolution this year was, “Resolved: The United States should legalize all or nearly all of the following: marijuana, online gambling, physician-assisted suicide, prostitution, the sale of human organs.”

“Kansas was on the affirmative and Towson was on the negative,” said Kelsie. “Kansas argued that the figure of the prostitute is racialized and stigmatized, and that we should affirm the figure of the prostitute to disrupt respectability politics which hurts sex workers as well as women who are not sex workers but are then slut-shamed and solicited for non-consensual sex.

“Towson argued that the politics of the affirmative was one which tried to normalize stigmatized groups rather than challenging the entire system of normalcy which makes some people stigmatized in the first place,” Kelsie added. “We challenged the aesthetic politics of the affirmative and argued that instead of focusing on sex work as purely an issue which affects women, we should understand prostitution as an abject position that is powerful in its own right. We called this different kind of politics that rejects normalcy ‘black anality.’

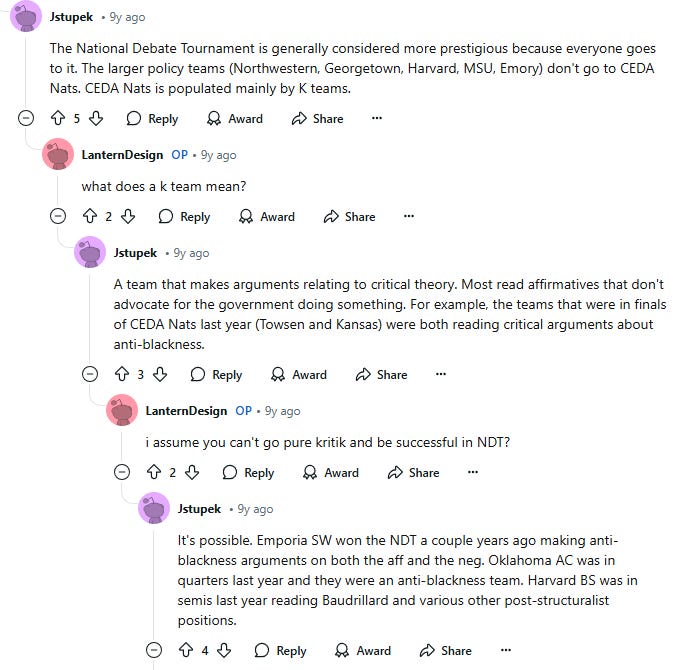

Theory is a major problem with CEDA, the debate association in which Towson won, though it isn’t limited to them. Quite a few debate organizations regularly feature theoretical arguments that challenge the assumptions of the question, or the nature of the debate itself — in fact, quite a few people on debate forums agree that CEDA teams actually use theoretical arguments better than those in other associations. But not all competitive debate organizations are quite so over-the-top, at least not most of the time. For instance, there’s CEDA’s sister-organization, the National Debate Tournament (NDT). CEDA and the NDT “merged” at some point in the 1990s (although this claim is somewhat controversial), and it’s typically the Ivy League schools and other more prestigious universities who compete in NDT, arguing more directly about policy, while CEDA tends to feature so-called “K-teams,” or teams that specialize in relying on kritik AKA theory. This discussion on Reddit is illuminating:

That exchange took place nine years ago, but I’ve seen little reason to believe that anything has substantially changed (though if you’re aware of any changes that have taken place in recent years regarding the use of theory, don’t be shy about chiming in using the comments section).

III. Tactic #2 - Spreading

So much for kritik. The second silly tactic that the Towson team used in 2014 is far more common — indeed, essential at the top competitive level for policy debate — and arguably far worse. It is known as “spreading,” a portmanteau of “speed” and “reading,” and the gist of it is quite simple: the competitor reads from a pre-written argument really, really fast. If you believe that the Towson video is only embarrassing because of the “wokeness” of its competitors, I would beg to differ. Take a look at this video of a CEDA final round from 2010, and compare the speaker’s normal voice to his debating voice:

Attempting to understand everything this gentleman was saying, I extracted some of the audio and reduced it to 50% speed:

It becomes a little bit more intelligible, sure, but not by much. He seems to be talking about secrecy, the ontology of the state, and something about a “tangle of discursive phenomena and official rhetoric.” I think, anyway. Later on, he says something about a “cultural imaginary.” It could be a brilliant argument, for all I know. But what does any of this matter if his speaking voice sounds laughably ridiculous? For comparison, the debaters on the Dartmouth team are seemingly less theory-oriented, but they still don’t sound much better.

In an opinion piece, one former high-school national debate championship winner explains its rationale, even going into detail about why various attempts to fix the practice and make it look less embarrassing to the average person have largely been fruitless:

As Policy Debate grew in popularity, the more Machiavellian debaters attempted to gain an edge by overwhelming their opponents with as many arguments and as much supporting evidence as possible. This was because if a team “dropped” an argument by its opponent—if it did not respond to the other side’s claim—that argument was conceded as “true,” no matter how inane it was. Chief among the strategies exploiting this rule was “spreading.” […] Their speeches often exceeded 300 words per minute. (A conversational pace is about 60 per minute.)

Debaters started formulating outlandish arguments. The more apocalyptic the outcome the better, with little care for the argument’s probability or real-world application. “A new retirement program will trigger a nuclear war.” “Prison overcrowding would cause the destruction of the ozone layer.” High school debate had come to this.

[…]

High school debate today is basically an intellectual game, not an exercise in truth-seeking. It has been turned into something that can easily be scored. This eliminates the complexity and intricacy of real discourse about real issues. If debate is a game, then the execution of a “spread” is like a well-timed blitz in football. Convincing a judge that your opponents’ arguments would cause human extinction is equivalent to a successful Hail Mary pass.

I doubt that any judge is actually being “convinced” of anything, but that piece is otherwise quite good, and it’s worth reading in its entirety. Its most intriguing claim is that any time people have tried to intervene and make debates look less absurd to the common person — the billionaire Ted Turner, for instance, even funded an organization called Public Forum with this exact intention — a process of erosion has taken place, leading inevitably to people talking faster and faster, sometimes while making dubious arguments rooted in critical theory (and behold: the 2021 opinion piece I linked above did indeed concern the same Public Forum debate organization). Anyhow, from my own research, just about every source has indicated that spreading has become a fully accepted part of competitive debate, and the controversy surrounding it has in fact waned, not grown. Spreading has won.

Sports analogies like the aforementioned “Hail Mary pass,” by the way, are quite common in these sorts of arguments about the nature of debate, but they’re often used by competitive debate insiders to uphold the status quo. Time and time again, you’ll find discussion online in which someone goes, “Why do you guys insist on looking so ridiculous? I thought the whole point of debate was persuasion.” And then the debate insiders will performatively show off their weariness with the question, insisting that outsiders just simply don’t get it. They’re acting like spectators watching a sport whose rules they don’t even know. But even when someone fully understands the nature of competitive debate, these analogies persist. Here is a good example of the kind of response you’ll often see:

Your focus on spreading, rather than a holistic look at CX [policy debate] as an event, is misplaced. I don't think that anyone is under the delusion that spreading, by itself, is a useful skill for most careers (auctioneering excepted) or personal interactions. But this is like complaining that linesmen in American football are learning useless skills because most jobs don't benefit from standing up and shoving someone. Or that basketball teaches the "non-transferrable skill" of dribbling.

But there’s a very obvious problem with sports analogies of any kind: sports-specific skills are taken by the general public to be valuable in and of themselves, and that’s why money goes into them. That’s why people spectate. And when enough knowledgeable fans have taken issue with a practice in a sport, the league will typically change its rules to make the sport more appealing. In basketball, for example, Wilt Chamberlain alone prompted the NBA to make several rule changes, like widening the lane, banning inbound passes over the backboard, and forcing free-throw shooters to keep their feet behind the foul line. In 2024, the NFL banned “hip drop tackles” because too many people were exploiting them. In drug-tested powerlifting, a rather unprofitable sport with almost no paying spectators, videos of bench pressers with extremely small ranges-of-motion kept showing up on YouTube “cringe compilations,” and so the IPF (International Powerlifting Federation) changed its rules so that the range-of-motion would increase. Pretty much all sports, even the obscure ones, take pains to make themselves seem respectable in the eyes of the masses. The overall attitude I find from competitive debate insiders, however, betrays the opposite intention: they not only want to be held completely unaccountable to the general public, but they don’t even want to appeal to it in any way.

IV. Conclusion (of part 1)

What we’re left with, in the end, is a practice in shambles — both at the high school and the college level. Moreover, it’s a reflection of America’s total disdain for the western rhetorical tradition, as this kind of debating does seem to be a uniquely American problem.

And in fact, sadly, my discussion will have to continue next week with a focus on that particular problem, since the fall of rhetoric has deep roots. My intention in writing about competitive debate was to situate its current state of affairs within the broader history of western rhetoric and pedagogy starting from around the sixteenth century when its role in education was first considerably jeopardized. But unfortunately, this is proving to be a more research-intensive task than I had hoped, too much for a single blog post. Still, I’ll conclude this week’s installment with a cautiously optimistic statement.

I actually do not believe that competitive debate is unsalvageable. In fact, it seems like something that could be quite effectively reformed if people had the political will to do so. Ever since the Republican presidential victory in 2024, conservatives have been aware of some sort of “vibe shift” that has allegedly occurred, assuring everyone of the absolute destruction of “wokeness” and other such ideological “mind viruses.” Well, progressive ideology does seem to be on the decline in the corporate world, but I don’t see any reason to believe that it has been purged from NGOs, academia, or the broader education system. It all seems pretty well ensconced.

Competitive debate, however, strikes me from the outside as a relatively weak, fragile enterprise — probably poorly-funded, as mentioned before — and thus filled with associations and institutions that could either be reformed or displaced altogether via hostile takeover. It also seems like something that could be wholly transformed on account of the fact that its problems aren’t strictly political but also largely aesthetic as well. I am no political strategist, and I don’t pretend to understand how money works. But it seems that in recent years, these organizations have more or less burrowed themselves into a hidey-hole because they are fully aware of how repulsive they appear to outsiders. Funding a successful alternative institution that isn’t afraid of being answerable to the public therefore does not seem like an impossible task.

Ultimately, I suppose, the fate of competitive debate really does lay in the hands of billionaires and hedge fund owners, but I would at least encourage normal intelligent people with healthy instincts to envision a world in which the average American actually considers competitive debate to be cool and interesting; something that people might even pay money to see. Imagine a debate competition in which the teams all dress respectably, speak understandably, strive to be charismatic and appealing, demonstrate an advanced familiarity with logic, and incorporate the skills of classical rhetoric into their speeches, including well-placed topoi and other techniques found in manuals such as the Rhetorica ad Herrenium and the Insitutia Oratoria. And most importantly, imagine a situation in which high school students could note their involvement in that kind of competition on a college application and have it count for something. I believe that such a thing is attainable. If Ted Turner invested a bunch of money into the aforementioned Public Forum organization back in 2002 and it’s still quite prominent today, I don’t see why a better, more stable one couldn’t be created now.

Stay tuned for next week, as I go deeper into the history of rhetoric, pedagogy, and schooling, and even make some broader conceptual points on media ecology.

The problems you're addressing could likely be solved if a culture of discourse was cultivated from the ground up. At my house we have a tradition of discussing a question on Wednesday nights at the dinner table. Every week another member of the family gets to propose the question, and the talk proceeds almost like a very informal debate. We don't choose sides or anything like that; we just talk about the question. Perhaps the problem lies in the "formal" nature of these debates, where points are awarded for arguments not given a rebuttal and other technical aspects. Excellent overview and I'm looking forward to part 2.