In Defense of Conservative Philistinism

Particularly in regard to the visual arts. Featuring some discussion on Robert Hughes.

I.

Every now and then on social media, a conservative art-themed account will post a picture of ugly modern art to demonstrate how badly the west has fallen. The idea is, you see the picture of the Jackson Pollock painting hanging in the museum, or the Tracy Emin readymade installation or whatever, and you say to yourself, “Oh, dear… the left has brought us into a state of advanced decline… how will the west recover… all is lost…” and then you keep scrolling, forgetting about what you’ve just seen around fifteen seconds later. These posts are, of course, tribal identity markers. You build up your sense of who you are by indulging for a moment in what you decisively reject. All groups build up their collective identity by distinguishing what’s good and what’s bad, and art continues to serve in that function, just as it always has.

But these conservative social media accounts also serve a second function: they continue to canonize these works and ensure their enduring legacy. The reason the artworks are supposedly important is because they’re supposed to be provocative. And for a while, such art really was. The conservatives are in a certain sense aligned with the original modernists who believed in the power of art to shock and elicit angry reactions. They’re essentially playing a nostalgic role for a drama whose suspense has long since subsided, and in this way they keep the flame of hope burning for any artist who dreams of the ability to disrupt the status quo. I certainly wouldn’t have to see any of this stuff almost ever anymore if it weren’t for the conservative critics.

One might ask why these people don’t simply post things they like, but the social media conservative art critic is in a bind. Right-wingers can’t really agree about what’s good. They know what they don’t like, but they have no idea what they like, and so they often have no choice but to define themselves through what they reject. Instead of being the action, they amount to a reaction, and it couldn’t be otherwise. I can even prove this. A while back, a Twitter account called CultureExploreX decided to make a thread of sculptors that he considers examples of how the west is, in fact, thriving, not dying!

It got decent enough engagement, but it also got an incredible amount of angry quote-tweets by some of the intellectual right’s biggest influencers and tastemakers, all of whom decried the poster for embracing kitsch, mediocrity, and other forms of detritus from our current managerial neoliberal postmodern artificial pornified Instagrammified (etc.) society. I have no idea who the person running the account actually is — for all I know, it’s just another corporate engagement-farming account located somewhere in India — but the artists featured really aren’t that bad for the most part. Some are pretty weak, sure, but a few of them I found pretty good, particularly Sabin Howard, Christophe Charbonnel, and Richard MacDonald, the last of whom has a gallery in Las Vegas, has done commercial work for the PGA and the Olympics, and caters to a clientele of various billionaires and major corporations, all of whom assuredly have quite superficial taste.

This last point, of course, is the whole problem. When people assess art, they’re not assessing a given work as a standalone object or phenomenon, nor are they even concerned much with the technical skill of the artist, but they’re rather assessing it within a specific context, a rhetorical framework. If you’re the kind of artist who impresses rich simpletons, it doesn’t actually matter if you’re good. The apparently low quality of the audience must mean the opposite. Of course, rich simpletons have been buying mediocre avant-garde art at exorbitant, record-setting prices throughout the last couple decades (a Basquiat, Warhol, and Rothko painting each sold for over $30 million just this year), but never mind all that. The point is, if you’re a true Le Artiste, you can’t look like you’re just some corporate sellout.

I’m generally a fan of unpleasant, difficult art that irritates both friends and family members alike, so it always feels strange to mount a defense of conservative philistinism. But there are times in which I think this must be done due to the excessive zeal of the True Art Enjoyer, the urban sophisticate. He’s often blinded by a desire to play the role of the embattled aesthete fighting in a war for the human soul against the forces of ignorance, even when absolutely nothing is at stake. This is one of those times.

II.

Most of the people who attacked the art works on that list probably wouldn’t have had a problem with them were they to appear in a different context than that of “high art.” Let’s say, for example, we found some high reliefs by Hossein Behzadi (pictured below) in the set design for a film about a deranged hippie cult leader, and those works line the walls of the cult leader’s mansion. I don’t think anyone would have a problem with them, then. Quite the contrary, the same people who were whining about his work just a while back would probably praise the art design of the film, admiring its firm commitment to detail. After all, the reliefs would be featured within something whose interpretive context is predetermined — an unqualified plus, because trust me, there’s nothing that the soi-disant art connoisseur hates more than having to use his imagination when assessing art. By giving these works a narrative dimension and thus tincturing the expected reaction (in this case, with irony), then through the power of spoon-fed suggestion, now they aren’t half bad!

Similarly: people found the art of Luo Li Rong particularly offensive, as they felt it indicated the growing superficiality and/or pornographization of society — as if anything that looks attractive in conventional 21st century terms or inspires feelings of sexual lust must be invalid on its face (for the sophisticated aesthete, popping a boner is the ultimate sign that the work is invalid — you don’t want to actually feel anything!)

But again, if they saw these works in a non-highbrow context, they probably wouldn’t be complaining.

Let’s pretend you’re going putt-putt golfing with the kids, so you go to an Ancient Rome-themed putt-putt course, and of course there’s dyed-blue water and little columns everywhere, and you see about a dozen replicas of Rong’s statues at various places, all of which look like the above image. The strangely full-bodied dress of that one in particular, Eclosion, is hovering over the green of Hole #09. Would you seriously pretend that the statues don’t look cool and exciting in such an environment? You’d probably stare at all of them for a couple minutes each, considering them a most welcome surprise, never thinking once that there’s any problem that must be resolved.

These aggressive denunciations of our engagement-farming Indian Twitter friend, it must be said, are coming in part from a place of intellectual insecurity. But that isn’t all. They’re also coming from being accustomed to a world in which artistic images are ubiquitous and cheap, and thus technical skill and discipline count for little, if anything. Skilled and disciplined images are everywhere, and they dominate the commercial market. The commercial market is tawdry and indulgent. Art should be something more. The high art connoisseur therefore carries within him a tacit acknowledgement that if a piece of art is truly high art, i.e. something more, then it shouldn’t merely please the senses. It must feel appropriate for a museum — or a respectable, cosmopolitan, white-walled mega-gallery, which I’ll henceforth subsume under the label of “museum.” And if it seems like it should fit in such a place, then it should be something that the average normie wouldn’t really understand or appreciate. It should be as far from “kitsch” as possible, and kitsch typically means something immediately gratifying.

III.

Let me try to explain what distinguishes proper art from “bad art.” Art snobs share Kant’s aesthetic views in a couple key ways. For one, they separate beauty from utility. For another, they share the belief that the aesthetic experience contemplates the object as a standalone item, often ignoring the role that perceptual context plays. But they differ immensely from Kant in one important way, and it’s in his idea that the aesthetic experience is essentially non-cognitive. For art snobs, the aesthetic is purely rooted in cognition — rudderless, wandering cognition — and it extracts value from an artwork mainly as a discursive task. If the work looks pleasing to the eye, we can call that a nice bonus, but that really isn’t the point. The point is that a good artwork doesn’t manipulate the emotions or compel an aesthetic response without eliciting some cognitive effort from the viewer. And, as it happens, our society has designated the museum to be the place in which this allegedly superior mode of art appreciation must take place. The museum is the refuge we’ve collectively designated for this type of art appreciation. The museum is itself a kind of medium, and here it’s the one through which an artwork attains its true meaning. Only through the museum can the full significance of a true, non-kitsch creation come into relief.

Of course, there are other places where art goes. There are small private galleries; and there are public art installations, sculptures, and unusual architectural works in/of state-funded buildings and various public outdoor areas; and the ultra-rich now spend more money on paintings than museums themselves do. But the idea of the museum always remains within the highbrow art appreciator’s mind — if only as a memory, or a target, or just a vague notion. When some dullard billionaire decides to purchase an ultra-expensive abstract expressionist painting, the idea of the museum lurks in the shadows of his thought process. The same goes for when an educated person assigns aesthetic value to a sculpture, like those supposedly bad ones above. The unstated question that always informs the assessment is, “Would it belong in a museum?”

And, well…? Would it…? Well, let’s consider a few situations in which it would. If the work is historical, then of course the answer is yes. There’s no utility in the historic. The “pastness” of the past belongs to its own distinct category of human understanding, and the museum’s role is to house the various objects that contain this feeling of “pastness,” which then further renders the feeling official. Of course everything from “the past” is still with us here in the present; an object’s “pastness” is essentially an illusion, even though it really was made in such-and-such a year. But much like church during the medieval period, the museum’s role is to take us to a place outside of normal worldly time, a realm wherein the past can be channeled through the present.

If a work makes some sort of political statement, then this too would make it acceptable for a museum. Politics are conceptual; they’re reducible to the essay format. All of this is well and good. But the work’s politics must be at least implicitly antifascist. Anything pointing in the other direction simply cannot work. Works that deal with the therapeutic are also perfectly acceptable. Works that deal with trauma are particularly welcome. The key to such works is that they should appear provocative and dangerous while remaining fully benign and non-threatening, at least from the government’s vantage point. The more the artist can increase the tension between those two poles, the more appropriate it is for the museum.

And then there are works whose value is determined mostly by the fact that they’re in a museum, or at least could conceivably one day be in one. We call these works “Modern Art.” The fascinating thing about modern art museums is that they contain works by quite a few artists who were completely opposed to museums when they were actually alive. The Futurists and the Dadaists in particular hated museums and wanted to destroy them. And their works, along with a broader array of modern art movements, were similarly meant to be provocations against the complacency of the bourgeois class, the guys who brought us museums, which are, of course, an enlightenment phenomenon, about 250 years old.

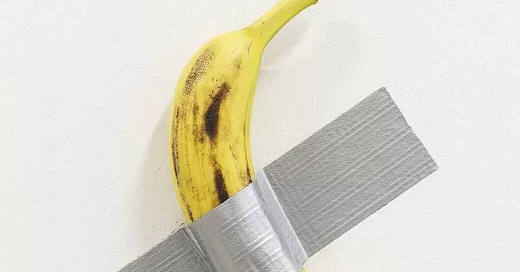

Many of these modernists felt that the museum was something for the artist to ridicule with his art. Marcel Duchamp in particular (who was indeed a genius) created the first “readymade” in the form of a urinal, the “Fountain” from 1917, and conservative art critics are still promoting it (via outrage) to this very day. His point was to make a statement on the art world itself. It was a joke, basically. But as we can see from the picture of that banana at the top of this blog post, which sold for over $100,000, people have been making the same exact joke for over 100 years now, and any semblance of humor has long since vanished. At least Duchamp had many other genuinely provocative ideas that would still fascinate someone if you explained it to them over a couple beers.

IV.

The key to understanding most modern abstract art is in A) its decontextualization from ordinary circumstances, and then B) its recontextualization into the framework of the museum. You take a concept that no one would typically care about or think much of, but then merely by presenting it as a high object of serious contemplation, you imbue it with some kind of artistry. The artwork’s meaning depends upon its self-presentation as art, with the museum as its implied final destination. But without any hope for a museum to validate it, the work’s meaning vanishes. In the eighth and last episode of Robert Hughes’s 1981 BBC docuseries The Shock of the New (based on his 1979 book of the same title), Hughes singles out minimalism for criticism along these lines:

This piece by the American sculptor Donald Judd, if you saw it outside the gallery, is just a row of plywood boxes. What the museum gives it is a slot in the debate about the nature and limits of art. And that was the content of the work.

Absolutely right. But in truth, the same basic principle applies to so many other styles, including the found-object installations of Robert Rauschenberg, whom Hughes champions as an example of a true artist. The Pop Art movement on the whole, which Rauschenberg helped influence, is an excellent example of what I’m describing. What separates a Warhol from a typical celebrity display is that he made silkscreen paintings, put them in galleries, and used repetition, which gave the critics a vague sense that he had something to say. What separates a Lichtenstein from the comics he shamelessly pilfered from (without ever compensating the original artists!) is that he blew them up, imitated the print dots with a kind of painting grid, and put them in a gallery. All the way down to Jeff Koons, what chiefly separates the work of the Pop Artists from a typical kitsch painting like a Velvet Elvis or those dogs playing poker, or a kitsch ornament like those lawn gnomes, is the pretense of their work being art — which is, of course, evinced by them being made for museums.

Essentially, modern abstract art attains its significance through conceptual circularity. It’s art because the artist is getting away with it. Why, pray tell, is he getting away with it? He’s getting away with it because it’s art. And the museum is the vortex that houses this circularity.

The same principle here also extends to most abstract expressionist paintings. But the justifications can become a bit more defensible, if misguided. If you take, for instance, Cy Twombly’s big painting of red swirls (pictured below), a typical gauche simpleton would say, “Duhhh, my eight-year-old daughter could paint that! A-hyuk!” And then the Twombly-defender could make the case that by focusing the viewer’s attention on the profundity of the bold color and texture of the swirls themselves, the painting can give the viewer a heightened appreciation for something as simple as swirls. It prompts him to emerge from the museum and view his eight-year-old kid’s scribbled nonsense anew, with a heightened appreciation — as if he’s seeing it for the very first time.

This isn’t an altogether bad point, since at least it refers to art’s ability to defamiliarize what’s familiar — something we find in great poetry, as the Russian formalists understood. But the problem with this interpretation is that the gauche simpleton can always fire back, “Well, I love my eight-year-old’s stuff, but I just don’t wanna see that shit in the museum! I can appreciate it at home!” and then there’s really just not much to counter that with. I have to confess, I agree with the gauche simpleton in this case. If I can already take aesthetic pleasure in simple, everyday things like red swirls, what need have I for a museum to bother me with abstract questions about their deeper meaning? The experience isn’t aesthetic but rather anti-aesthetic.

Let me draw a parallel. I once saw a debate break out between someone who really enjoyed Japanese noise music and a guy who didn’t enjoy it at all. The guy who didn’t like it said,

You know, I enjoy all kinds of noise, but to me, the best noise is when I’m driving my truck, and I open up the window juuust a little bit, like this much, see. And then the wind starts to come in, and you can hear it howl just a little, like some kinda ghost. And the deeper part of the noise stays there, you know, like a hum. It’s like two sounds are going at once. And if it starts to rain, and I can turn the heater blower up a bit, well, then you know, goddamn, I’ve got the best setup you can imagine. See, I don’t need to pay $16 to some Jap for a tape cassette filled with noise, nah, I’ve got the best noise I could ever need when I drive.

And then the first guy told him something like, “Then you will never understand what noise is all about!”

But speaking as a guy who enjoys Merzbow, C.C.C.C., The Incapacitants, Pain Jerk, K2, and a bunch of other Japanese noise acts, I think the second guy understood noise completely. Far better, in fact, than the first. He found a good sound that he enjoyed and didn’t feel the need to seek out anything else. If the first guy couldn’t understand that, then I consider that a very good sign that he doesn’t actually enjoy listening to this stuff but rather considers it a kind of “art music,” a way of disciplining himself instead of simply appreciating the finer things that life has to offer.

V.

The decontextualized logic and circularity of modern art has been around for quite some time, as we’ve seen, but in today’s media environment, even the purely conceptual food-for-thought that modern art was supposed to offer is being expressed better in lowbrow channels, at least for anyone who has the ability to take his surrounding environment seriously. Since modern abstract art can typically result only in a rather bland and irresolvable debate about what “art” means, or what its role in society is supposed to be, even the more interesting questions about consumption and commodification that it supposedly raises are being better explored in the places that lack artistic pretense.

Let me give an example. In 1961, Piero Manzoni produced about 90 cans of his own feces (supposedly) and labeled it “Artist’s Shit.” The cans of shit were bought for exorbitantly high prices and wound up in museums. Again, please do remember that Duchamp was doing this sort of thing back in 1917. The joke was being refined, sure, but there was no innovation. But then, some decades later in 2019, an attractive British cam-whore named Belle Delphine decided to mass produce and sell 600 plastic bottles labeled “Gamer Girl Bathwater” for $30 each. They all sold out within three days. The latter situation, despite having no artistic purpose, is far more conceptually interesting than the former, since the bottles were not being sold to pretentious art collectors (many of whom were already engaged in speculative purchasing by that point) but rather to everyday people, and there was at least some implied utility in the latter item. Whatever their motivations may have been, people were buying the Gamer Girl Bathwater because they really were intending to enjoy it.

A similar parallel can be drawn between Damien Hirst’s rather meaningless yet extremely expensive jewel-encrusted skull and the extremely gaudy chains worn by various rappers. There is far more profundity in the fact that Waka Flocka Flame had a custom-made jewel-encrusted Fozzie Bear chain that he’d wear in public at one point (Gucci Mane also wore a Bart Simpson chain) than anything a pointlessly expensive jewelry-based modern artwork could ever offer. Indulging in decadence means absolutely nothing from an artistic standpoint when your clientele is itself already decadent and shamelessly so. And turning the museum into a house of decadence means nothing when the public already understands it as such in the first place. Decadence is only interesting when the pretense of artistry is altogether lacking.

A third example: artists got into performance-as-art during the 1960s as a way of confronting “the fetishization of the object,” often themselves using exactly that language. For instance, the Marxist performance artist Stuart Brisley would do things like come extremely close to drowning in an underwater tank, capturing the process on video. Various kinds of “body art” were also being done, notably by Arnulf Rainer among others — something Marcell Duchamp had already done when he shaved a penta-star into the back of his head. “Happenings,” which I’ve discussed elsewhere, also were in vogue. But again, once the art world fully embraced these provocations as legitimate art forms, whatever meaning they could have had became fully subsumed within the circularity of the museum. Such provocations are far more interesting in the context of the mass media, even in early examples like the magic and escape artistry of Houdini. As for contemporary examples of extreme body degradation being done for commercial purposes, I’m sure you can think of plenty without my help.

By the year 2008, the aforementioned art critic Robert Hughes had gone from discerning skepticism about the direction in which modern art was headed to full-blown pessimism. He wrote and directed another BBC documentary, this one called The Mona Lisa Curse, about how the art world has been completely captured by the logic of the marketplace and thus dominated by the lucre of fools. He summarizes his thoughts near the very end:

Some think that so much of today’s art mirrors and criticizes decadence. Not so. It’s just decadent, full stop. It has no critical function; it is part of the problem. The art world dutifully copies our money-driven, celebrity-obsessed culture — the same fixation on fame, the same obedience to mass media. It jostles for our attention with its noise and “wow” and flutter.

This is pretty much right, except for one thing. Hughes, up to his dying day, blamed money and finance for the problems afflicting the art world. He understood that technology was a factor in what was rendering the high arts less and less meaningful, but he felt that money held the greater responsibility.

In the seventh episode of his Shock of the New series, he specifically disagrees with Marshall McLuhan’s claim that the artists are rebellious figures because they choose to live in the present, by which he meant that they remain engaged with the possibilities of the technological environment surrounding them. Indeed, Hughes seemed to consider McLuhan’s then-heralded status as “prophet of the new media” obscene on its face. For him, the banality of Andy Warhol is something perfectly compatible with McLuhan’s thinking, because Warhol was essentially trying to fuse himself together with the mass media, and in many ways he succeeded. For Hughes, there’s nothing profound or heroic about that. On that point, he wasn’t wrong.

But what Hughes failed to realize is that McLuhan wasn’t necessarily making an evaluative statement about the figures we conventionally consider “artists.” McLuhan’s understanding of history was far too rich for him not to have recognized that the definition of art is contingent; that it changes over time. Instead, McLuhan was proposing a novel definition of “artist” that so happens to overlap significantly with our western literary canon. But a novel definition means that if it doesn’t describe you, then you don’t fit the bill. Understood this way, it isn’t that McLuhan was looking forward to hacks like Damien Hirst or the guy who made the “Piss Christ” and saluting them as the future’s great heroes. In my view, McLuhan’s own thinking should tell us that they don’t count as artists at all. McLuhan believed in Ezra Pound’s quotation, “The artist is the antennae of his race.” A Jeff Koons is the orifice of his marketplace.

If we pursue the insights of McLuhan’s media ecology even further, we might as well also recognize that the museum never could have remained the sine qua non of true artistry. Itself a relic of the enlightenment bourgeoisie, we have to recognize the museum for what it is: namely, a lingering byproduct of the age of print and thus itself something of an historical curiosity. In the same way that the printed word fixes information and confines it to a decontextualized locus, so too does the museum, only with three-dimensional images, which themselves are tactile (at least in theory) but never meant to be touched. And as the world of the media advances, what we find in the museum increasingly loses its punch. In The Mona Lisa Curse, Hughes makes the argument that when the Mona Lisa first came to America in 1963 and was shown in the Metropolitan Museum, it merely represented a facsimile of what it had been in the Louvre, the museum from whence it came. But I have friends who have been to the Louvre and have seen it there, too, and they tell me that the whole experience of viewing it is quite contrived and artificial. Downright unsatisfying. The Mona Lisa would appear to be a facsimile anywhere because it’s an iconic representation of how we see it in the digital realm. Not the other way around.

As ignorant as today’s conservatives might be regarding regarding the broader world of culture, I don’t think they are wrong to perceive this same kind of artificiality that the museums bestow on their most prized items. They might reserve their complaints only for a certain “look,” but they’re not wrong to recognize something empty at the heart of what people are calling art.

Sort of unrelated but Ben Werther and Aaron Moulton are doing great stuff in the high art world.