I.

I’m a believer in the idea of being self-taught — not just that it’s a good thing, but also that it’s a legitimate concept in the first place. Autodidacticism is an idea that we could dismantle and criticize all day. After all, learning always requires active effort, so isn’t everyone an autodidact? No human can merely be a passive information receptacle, even at the most elementary level, yes? And also, the whole idea of getting an advanced degree is that the student learns to be an independent researcher, i.e. an autodidact — no longer prodded along by a teacher who quizzes her, tests her, and assigns her busywork at every turn. So the concept is useless. Right?

Well, no, because if you spend some time around people who have gotten an advanced degree, you’ll find that a whole bunch of them have no intellectual curiosity whatsoever. They went up to teacher and said, “Tell me what to do, teacher, and I’ll do it!” and then the teacher said, “That’s the spirit! Now do this!” and gave them a list of books to read, hobs to nob, and butts to kiss. They then replied, “Yes, master!” and that’s basically how it went. Most of them have composed a thesis that could have been written by artificial intelligence, and the most ambitious ones plagiarized liberally while focusing on schmoozing and networking (the real way career success is made). Exceedingly few of them once thought about going beyond the little fortress of books that their committee built for them, and still fewer actually did. And so for that reason, the concept of autodidacticism is quite safe. The vast majority of people who went through school all the way to reaching a terminal degree were not literally filled with information like a gas tank at the pump… but they might as well have been. They are not autodidacts.

There are also people who never once went to school, tried to teach themselves something, and yet still are not autodidacts simply because they attempted to simulate the exact experience described above. These kinds of people spend their days with a list lodged in their heads of things that smart people are supposed to do, read, say, and believe, and they do everything they can to stay faithful to that list (updating it as needed, since its contents are quite fickle). Because it’s pretty easy to go to school, these people are not as common, but they are real, and they’re some of the saddest souls you’ll ever meet. They inherit the worst of both worlds: not only do they miss out on the feeling of grasping the illusory brass rings of academia, but they don’t even get the compensatory joy of discovering anything interesting for themselves, since the brass rings are all they really yearn for. They’ve been swindled into believing that the grad-school slop canon of Marx, Freud, various feminists, critical theorists, and French poststructuralists is just like the bourgeois literary canon of the New Critics, something that (about seventy years ago) would earn you symbolic capital simply by having read it, regardless of your social class or education status. But of course, these two things aren’t the same, and the first canon is mainly a transactional status-conferring tool within a specific industry, not society at large. Unable to see that, however, these people typically just stick with the grad-school slop and forbid themselves the pleasure of indulging in anything genuinely interesting, unsupervised, psychedelic, stomach-churning, “debunked,” or “outmoded” — something a true autodidact would never dismiss outright.

Being an autodidact, at the most basic level, means that you are free. Let’s say you want to consult some notable figures on the question of love and eros. You can take, let’s say, Plato, Saint Augustine of Hippo, Rumi, Dante, Soren Kierkegaard, Ludwig Klages, Denis de Rougement, Wilhelm Reich, and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, put them on equal footing, and decide for yourself who has the best insights, never once feeling the pressure to pay lip service to the intellectual authorities of our time. You can thus be an autodidact whether you’re formally educated or not. It’s really quite simple.

II.

Now, having said that, there are still tendencies with autodidacts that can put them on the fast track to dilettantism and casuistry, something we should consider deeply shameful regardless of whether or not they have attained “guru” status. And among those tendencies, I consider the reflexive rejection of secondary sources to be one of the most harmful. People with this tendency will often get into some area of intellectual inquiry (like metaphysics, political philosophy, a certain period of literature or world history, and so on), and then declare that they are going to focus solely on the primary sources, doing as much as possible to rid themselves of the pernicious influence of our modern historians and academics, with their predigested narratives and unreconstructed biases. Practically speaking, this means that if they buy a scholarly edition of some old book, they’ll completely skip the editor’s introduction or afterword, and even (if they’re particularly bold) refuse to read the footnotes or endnotes.

There is, to be sure, something understandable, even relatable within this mentality. Autodidacts strive to be pure and unblemished in their learning. They want to interact with a body of writings and feel as though they are fully in control of their own thoughts and interpretations, uncontaminated by the poisonous ideas of outside editors and commentators who typically have their own axe to grind. It’s fulfilling to know that if you have a certain thought on a certain subject, it’s something that you yourself came up with; it wasn’t just handed over to you by an interlocutor. And these kinds of autodidacts are definitely onto something. They’re not wrong to suggest, for instance, that academia has become an embarrassment, particularly in the 21st century.

Nonetheless, it remains true that skepticism towards secondary sources can be a major pitfall for autodidacts. And it can take a couple forms.

III.

One such form is the kind of skepticism that creates the desire to read every single writer directly before reading any kind of commentary on him. With literature, I think this is quite understandable… up to a point. Obviously, we read literature because we want the language to impress us. People have recently rediscovered an amusing quote from that movie Metropolitan in which some lame guy says, “I don't read novels. I prefer good literary criticism. That way you get both the novelists' ideas as well as the critics' thinking.” And yes, this is clearly absurd, especially when you consider that he’s saying this in the context of Jane Austen novels. The best literature isn’t even about “ideas” at all, if we’re being honest. It’s about style and poesy, or, often in the case of novels, psychological exploration. It’s about making the reader truly conscious of what was already known to her. But what exactly do you do when the literature is more or less impenetrable? Think of Ezra Pound’s Cantos — is it really so shameful to want some scholarly footnotes when you have no idea what Pound is going on about, and you can sense that there is in fact a distinct answer? Maybe you’ll want to keep it “pure” on the first reading, but if you find yourself enjoying the poetry, you’re going to feel yourself naturally growing curious about what each reference might mean. Moving further back in time, most of us will agree that Dante is great, but are you really going to read John Ciardi’s translation of The Divine Comedy, or maybe Robert Durling’s, and not pay attention to the notes? Even assuming that Dante was a great Man Against Time, someone who singlehandedly disproves the historicist view that everyone (no matter how ingenious) is merely a product of circumstance, you still should want to know the historical circumstances that Dante was actively opposing, since his poetry is inseparable from them.

Here’s an even more disturbing question: what if you decide to read a great classic of western civilization and simply find yourself not enjoying it? What then? The safe thing, and the first thing you’ll want to do, is to blame the translator. So let’s say you do that, and then you opt to read a more “authentic” translation of a text — something that really approximates what the original author was trying to convey. But then, for all that effort, you find yourself only hating it even more! At that point, do you just decide that you’ll pretend to like it in order to save face? Or do you perhaps conclude that the great classics of western civilization are indeed overrated and become some sort of libertarian who gets into coding and reads Richard Hanania’s blog?

This will deeply upset some, but I would advise studying the historical conditions under which the work was produced, if only to appreciate why things were conveyed so strangely. And this means, like it or not, reading some secondary material from the couch of degeneracy that we call academia. At the very least, you’d be better equipped to judge an ancient work within its proper context. In basically every era, there’s a compositional grammar that one should appreciate when approaching a text. People often accept this when it comes to music appreciation — I’ve never seen anyone try to claim that formally studying the sonata-allegro form wouldn’t make them more appreciative of symphonies. Yet people get weird about books.

I’ll nonetheless concede that the desire to approach all of literature as innocently as possible is at least understandable (if misguided)… but I can’t at all abide by this same attitude when it comes to philosophy. The prejudice against using secondary sources to understand philosophers, if only to assess the scholarly range of opinions and debates surrounding them, is an all-too-frequent source of awful thinking that you’ll find on the internet. It typically can be seen when someone wants to say something real smart about some major canonical philosopher who isn’t exactly known for his gobsmacking prose — think Kant or Hegel — and then he proceeds to read them by, say, listening to an audiobook of The Phenomenology of Spirit and then, right afterwards, the Critique of Pure Reason, all while playing League of Legends online. Or, alternatively, by taking some amphetamines and plowing through each book in one or two nights. Unquestionably, nothing valuable will come from any of this. Yet God knows people try it (they actually try it in grad school, too).

This mentality is almost always accompanied by the condescending dismissal of introductory academic books, the ones supposedly made for idiots. Think of, for instance, the Oxford Very Short Introduction series, or the Cambridge Companions, or those The Great Courses audio/video lectures… any book with the phrase “Core Concepts” somewhere in the title. You can probably think of quite a few of these sorts of texts. Yet for all the flak they receive, simply reading one would go a long way in preventing some of the truly bad interpretations I’ve seen floating around. And although this may disturb some people, I actually do believe that reading these kinds of “For Dummies” texts can sometimes even be more valuable than attempting to read the primary material, simply because the reader might lack the attention span and/or patience to absorb complex and often poorly-written ideas (let’s face it — many of the west’s greatest philosophers were horrible stylists). And he might not even want to engage with the material at length since it isn’t even foundational to his thinking, thus better taken as a potential footnote or some harmless grist for the mill.

I’ll even recount a personal example of when secondary material has prevented me from some serious foolishness, since I’m not above anything, here. When I attempted to read Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception about a decade ago, I thought I understood what it was saying perfectly well. But luckily, I also had a vague, nagging suspicion that I wasn’t getting everything. One brief introductory monograph later and, well, it turns out there was a ton of stuff I wasn’t getting, because Merleau-Ponty has a writing style that seems quite straightforward yet isn’t. The most important ideas can unobtrusively slip by while the reader is more dazzled by the psychological examples or case studies he recounts (one of which I threw into this short piece) to bolster his more subtle, carefully worded points.

IV.

There’s another problem with mistrust towards secondary sources, though, and it has to do with the slipperiness of the categories “primary” and “secondary.” Secondary sources are completely unavoidable, since just about everything that led you to the text counts as one. Where, for instance, did you first hear about Nietzsche? From a book? A YouTube video? A teacher? A friend? Whatever the answer is, it’s a secondary source, and the particular way in which Nietzsche is presented to you will tincture your understanding of who he is, or at least give you something specific to look for when you first read him. Translations, of course, are also secondary sources, and they too are never neutral. This is a problem that most people don’t even try to solve.

What autodidacts must realize is that attempting to remain as close as possible to the primary source while shutting off all outside interference doesn’t strengthen the reader inwardly. If anything, it’s quite the opposite. Even leaving aside the problem of translation: you want to understand what a great mind from the past said, so you read him as nakedly as possible, oblivious to all the ideas that you yourself are imposing onto the text, including broader social commonplaces that you’ve accepted your whole life via passive absorption. The point is, the desire to read an old book always enters into one’s mind through some kind of discursive matrix, and this matrix is itself a kind of secondary source. This is why any two “fundamentalist” branches of Christianity who claim to read the Bible purely ad litteram will often have wildly different interpretations of a given scriptural passage. There is no way to avoid the fact that everyone has an interpretive lens with a distinct set of characteristics.

Some autodidacts understand this problem, and so while they maintain a mistrust of secondary sources, it’s a bit more sophisticated; more qualified. They’ll be willing to trust an analysis that (for instance) seems like it might conform to their general worldview, or perhaps they’ll search for some explicative material, but only prior to a certain year or decade, which they use as a cut-off point. This approach is better than nothing, but it has its own set of problems. For instance, certain books will be vaulted to high levels of popularity despite having little scholarly value, simply because their argument is too exciting to resist. One example is Glenn Alexander Magee’s Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition, which argues that Hegel should be understood as mainly a Hermetic thinker, focusing in large part on his influence from Jakob Böhme as well as various alchemical and occult references in his work. This book has an incredible amount of internet popularity, but its academic reception has been mostly lukewarm to bad, with just about everyone agreeing that Magee’s conclusions need to be walked back considerably in order for the research to be acceptable. All the same, there’s now an entire school of wacky “intellectual historians” on social media who have declared that Hegel was a crypto-Gnostic who invented “wokeness” with his intellectual dark sorcery, and this book by Magee has formed a major cornerstone of their thinking.

All of which, I think, would be fine if it lent itself to a great work of art — some sort of powerful film, comic book, or heavy metal concept album about the life and times of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, his work with the secret societies such as the Freemasons and the Illuminati, and his mysterious Gnostic magick practiced therein. Something like that. But instead it leads to nowhere besides crankish internet political invective that makes the LaRouchies look downright reasonable by comparison.

Within this category of autodidacts who have a qualified appreciation of secondary sources, there are also many who appreciate “outsider scholarship” simply because it’s “outside.” It opposes academia, and that’s its main merit. These “outsider scholars” are pretty recognizable. They tend to cast themselves as scrappy underdogs taking on a corrupt and/or complacent establishment, armed with nothing but their dedicated research along with an unimpeachable love of the truth. This kind of narrative framing works well as a tactic to get the reader excited, allowing the otherwise dry process of academic research to turn into an exciting first-person detective caper. So it’s often used because it sells books. It moves units. (One of these authors actually first published her findings under a legitimate academic publisher, but then wrote a popular version of her research in which she still plays this outsider role — it’s just too effective to pass up!)

And occasionally, without question, these kinds of “outsider” books are right — just not as often as one might want them to be. But even if an argument seems a little too ridiculous to be correct, the temptation to feel as though you’re in possession of hidden, esoteric knowledge is too strong for many to resist. The anti-Stratfordian Shakespeare authorship theories wouldn’t be nearly as exciting if the academic consensus shifted and most of Shakespeare’s top scholars decided that Shakespeare really was Edward de Vere pulling some sort of elaborate trick. If that were to happen, an outsider group of autodidacts would emerge, arguing that these scholars are elitist lunatics and that Shakespeare was really Shakespeare. Honestly, I think they’d be right.

But that’s the temptation, in a nutshell. The autodidact wants to feel like an outsider who sees what the insiders cannot. For this reason, you’ll occasionally find them promoting scholarship that they otherwise wouldn’t care about, simply because the author has presented herself in this sort of mold. One amusing example can be found in a sweet old woman named Dolores Cullen, who wrote a book on Geoffrey Chaucer, arguing that he composed The Canterbury Tales as an allegorical riddle with a hidden esoteric meaning, one in which all of the pilgrims represent signs in the Zodiac while Harry Bailly the host represents Christ.

Some intellectual guru on Twitter aggressively promoted the video above as an example of how the outsiders are the real scholars who are doing the work that those dummies in academia are too lazy (or scared, or conformist, or whatever) to do. But speculations about Chaucer and allegory have been around forever; it’s widely known that allegorical thinking pervaded the middle ages. The main reason no one ever made her argument before is probably that it’s just not very convincing. When I look at Cullen presenting her research in that video, I get the sense that she’s an enthusiastic amateur who’s having a whole bunch of fun — maybe she read Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, found it very exciting, and wanted to find something equally exciting in Geoffrey Chaucer. But as charming as all of this is, the research is still quite bad. And the major thing that exposes its weakness is merely having some familiarity with some of the major books on Chaucer that have been around for decades. When I looked up academic reviews for Cullen’s book, one reviewer apparently felt so bad about trashing her work that she took a moment to praise Cullen’s enthusiasm:

It would be very easy for professional Chaucerians to scorn, or to ignore this chatty, somewhat eccentric book from a minor press. Cullen describes herself as first encountering Chaucer "as a middle-aged college student", and her written discourse betrays the novelty of her encounters with Chaucer and the world of scholarship. She charts, for example, her own frustrations and successes in her library searches ("I almost cheered"; "my face turned red. . . and I burst out laughing"). Such enthusiasm is normally edited out, just as, more seriously, most presses would have insisted on major rewriting to update Cullen's research and to modulate many of her conclusions. For these reasons, few teachers will want to recommend this book to their students, and I doubt it will very often be cited in scholarly articles. And yet I suspect many such teachers would be secretly quite glad if they could inspire their own students to write a series of three volumes on Chaucer.

This is actually much more damning than a thorough beatdown!

V.

I’m writing this post because I want autodidacts to be better than everyone else, and I think it’s quite achievable. But I also think it’s good practice to be skeptical of those who relish their outsider status, or who willfully deprive themselves of potentially good information because they’ve struck an anti-establishment pose. Therefore, I’ll conclude with a few pieces of advice for autodidacts who have higher aims than mere dabbling.

Approach the western canon of important books at your own pace.

By this I mean, do not feel obligated to pore through every single book that educated people are supposed to have read, one by one, in order. Instead, read what sounds interesting to you first. Martin Heidegger once claimed that in order to read Nietzsche, you first need to study Aristotle for a decade. And while I’m sympathetic to Heidegger’s philosophy, this really is loser talk. If you want to read Nietzsche, go ahead and read his stuff! You can come back to his main influences later on. You’re teaching yourself, here, which means that there aren’t any rules. Take advantage of your freedom. And if you aren’t familiar with something and haven’t yet gotten around to understanding it, you’re always free to bow out of any discussions that you overhear. “Better to be silent and thought a fool…” etc.

Don’t shun academic writing in general, especially if you’re trying to make real intellectual contributions.

The honest-to-god truth is, whatever insight you think you might have about a major western philosopher, artist, or literary figure, it probably has already been said by some egghead scholar beforehand, and moreover he said it better than you could have. For many naïve autodidacts who are just getting into the world of bibliophilia, that’s a hard pill to swallow. Academia is filled with some of the most potentially mind-polluting nonsense ever written, and the temptation is strong to dismiss all of it past a certain year or era. But at the same time, there are plenty of extant professors who are extremely boring individuals who are quite content to live in a little hidey-hole wherein they’ve mastered one extremely niche topic. The “woke” guys are the ones who get all the headlines (though many of them never get cited!), but about a quarter to a third of these professors I’d estimate are still fairly benign, nebbish people who actually want to do what they’re paid to do. They have one job, and it’s to know a lot of stuff about something. Respect the tenacity with which they cling to this one, rather mediocre job.

Don’t shy away from “For Dummies” stuff.

As I said earlier, there is nothing wrong with introductory material in principle, and this includes the editor’s introductions found in the beginning of books. If you can find a good solid monograph that sums up not just a certain thinker or topic, but also discusses the current academic controversies surrounding it, then you can prevent yourself from indulging in a lot of idiocy. This piece of advice, by the way, applies to tenured professors as well, many of whom have no idea what they’re talking about and would be well-served by a solid introduction to the material they’re supposed to have mastered — something their own clueless professors never gave them.

Don’t shy away from recent scholarship.

In graduate school, the principle you’re meant to internalize is that new scholarship will be better, since it will improve upon the blemishes and confusions of old scholarship. That’s a nice thought, but as most autodidacts will recognize, it’s pure nonsense. As academia has gotten increasingly politicized, much of the scholarship in the humanities has gotten dumber. However, this fact does not make the opposite principle true, namely that the older scholarship will always be better. In reality, things are more complex. While there are more blatantly ideological works dedicated to various aggrieved minority groups, bizarre sociopolitical obsessions, and so on, and they are quite easy to spot, there are also plenty of impressive scholarly works still being made that typically fly under the radar. For instance, ten years ago in 2014, a full translation of the Rigveda was published by Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton. It is quite simply the only good full translation of that text in all of English, as the only other one by Ralph T.H. Griffith is basically crap, and was even considered crap by the standards of his day! Great works of scholarship such as this do, in fact, still occur quite often, and you don’t want to deprive yourself of decent material just because of a glib assumption that what’s older is always better.

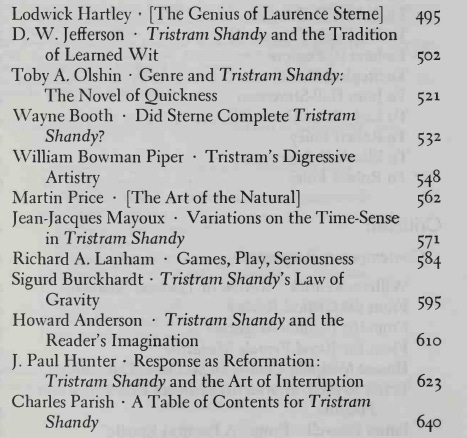

There are various ways to determine how the notable scholarship on a given subject has changed, and you’d perhaps be surprised by some of the developments. For example, if you get a Norton Critical Edition of some literary classic and there are two such separate editions, check out the supplementary scholarship in the Table of Contents for each one and compare the older one to the more recent. In fact, let’s try it right now. Look at the scholarly article titles from the 1979 Norton Critical Edition of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy edited by Howard Anderson:

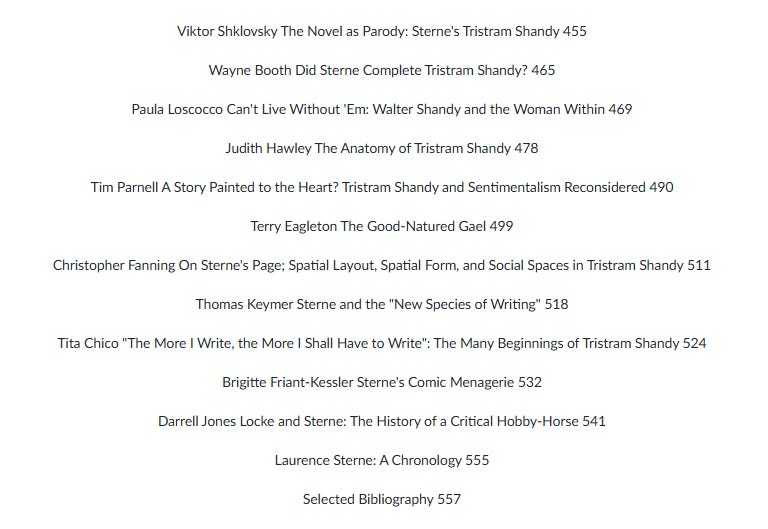

With the exception of the Sigurd Burckhardt article, these titles all allude to recognizable aspects of the novel, but they’re much more formalistic in nature. They’re dealing with literary technique, the anticipated psychological response of a given reader… that sort of thing. Now compare that selection of scholarship to the one from the 2018 edition edited by Judith Hawley (which I’ve screen-capped from the Barnes & Noble web site):

To be sure, some of these articles seem pretty stupid. “Walter Shandy and the Woman Within”…? Sounds gay to me, and it probably is. But there are other article titles that seem promising, or at least maybe interesting. Hawley, the book’s editor, seems to have written about the influence of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy on Sterne. Tim Parnell’s article features a discussion that probably compares Tristram Shandy to Sterne’s other novel, A Sentimental Journey. Darrell Jones has written a meta-analysis of the different academic treatments dealing with John Locke’s influence on Sterne. And there are a few articles that discuss the historical circumstances surrounding the text, including the book as a material object — something important for Shandy, since much of the writing was self-referentially experimenting with the medium of print. On the whole, both editions seem pretty promising. The earlier one seems designed to help you notice subtleties within the text you might have missed, while the later one appeals more to the principle of intertextuality — the idea of seeing that one book’s place within an intricate web of other contemporary works. I can’t judge which edition would have the better scholarship just based on the Table of Contents alone. And so, there’s no reason not to just skim through each one and decide what would be more useful for you.

You’d be surprised at how often it’s like this. Newer scholarship often contains useful information, but finding it can be inconvenient. You really are, if I can borrow the old cliché, looking for a nugget of gold within an entire cartload of donkey manure. The humanities has lost its way, this is certain; yet at the same time, there is a higher total volume of good scholarship being produced today than there was 100 years ago. It’s just that it’s being drowned out by a sea of much more noticeable, flamboyant, embarrassing nonsense. So while it might be hard to wrap your head around the situation at first, you eventually will realize that two things can indeed be true at once: the humanities has lost its way, and yet there is great work still being done in the humanities.

Have faith in yourself.

This is maybe the most important piece of advice, and it flows naturally from the previous paragraph. Ultimately, you have to rely on your own ability to tell the difference between crap and not-crap. Autodidacts may claim that they want to avoid most secondary sources simply because they want to preserve the purity of the reading experience, or maybe because they want to save themselves some time. But the worst reason, and I suspect a common one, is the fear that they’ll be somehow polluted by the modern world if they read what some limp-wristed soy boy has to say about a satirist from the Hellenistic period, or the Tao Te Ching, or Tantric Yoga, or whatever. In truth, the pollution is all around us, and there’s no avoiding it. Therefore, you must have faith in your own abilities to separate what’s bogus from what’s reasonable, and it has to be a faith strong enough to allow you to explore any argument, pursue any form of research, and engage in any kind of discussion with the “adults in the room,” never once crippled by the concern that you’ll somehow wind up tainted from the experience. If you’re afraid that there’s a “beautiful soul” inside of you that might be corrupted, you should test it by exposing it to as much corruption as possible. If it winds up broken, it was never worth much to begin with.

If you’re a true autodidact, then you’re free. And if you’re truly free, then you are in fact dangerous. And the most dangerous version of yourself is the one that demands to be taken seriously.