Rub It In

More on "right-wing art," and the ways in which an interpreting audience can change a work's meaning

I.

Last week’s post on the concept of “right-wing art” turned out to be pretty successful, and I thank everyone for reading and sharing it. Among such readers/sharers was the blogger Curtis Yarvin, whose recent debate with a Harvard professor is now available for viewing and whose antics are being covered often these days in the pages of the NY Times. In a tweet, he responded to my claim saying that Force Majeure can only be called a “right-wing” movie if it is understood as such by a substantial audience; otherwise, it’s just a black comedy by a left-wing Swede. He wasn’t particularly impressed:

Sorry but Force Majeure is absolutely a right-wing movie.

Come on let’s not be all Bishop Berkeley here. If a tree falls in the forest etc.

My late wife and I saw FM when it came out and we agreed it was super based and I don’t care if no one else was in the room

I’ll admit, I was initially irritated by such a glib response, but then I saw his Twitter feed and realized that at the same time he posted it, he was also busy arguing with about ten autistic people at once, all of whom were trying to accuse him of abandoning his old political philosophy by supporting the current Trump administration, or something like this. So, given those circumstances, I think it was nice of him to bother reading and responding to the thing in the first place. He certainly didn’t have to do all that!

Additionally, it gives me a nice enough excuse to expand upon some points I made previously, since he was probably voicing an opinion that quite a few readers share but didn’t bother to say aloud. So I’m going to spend this blog explaining why I’m right and why he’s wrong, and after that, I’ll make a more interesting point about audience and reception.

I’ll try to explain why I’m right as briefly as I can before giving some concrete examples. If the reader didn’t catch it, I’m being accused of subjective idealism (hence the Berkeley reference), but I’m not, and we don’t even need to go into metaphysics, because material things are material things, and I wouldn’t care to dispute that. However, all works of art are created as interpersonal communication, and communication begets communication. Even AI art is interpersonal because some person has dreamt up the prompt, selected the best result, brought it out to the people, and will continue to curate his computer-generated piece. The artist transmits the work, people see it, and they interpret it to mean something, whether they do so collectively or privately. Now, all material things in general, like rocks or trees, occur to us as communication as well, and their communicative significance will differ vastly depending on whoever’s encountering them: a flower won’t mean the same thing to a human as it will to a bee. But whatever it means to us, a flower’s material existence is pretty straightforward. Whatever rocks, trees, or flowers are, they’re there.

And in this case, likewise, no one is disputing that some work of art is there. It’s just as physically present as a rock, flower, or tree. But the point is that it’s doing stuff — stuff that we’re going to interpret as symbolically meaningful — and so the only way to make sense of its meaning will be through interpretation, since all symbols are conventionally determined. This is why animals, lacking the capacity for symbolic communication, cannot appreciate art as art. The work of art might affect us humans on a visceral, prelinguistic level (in fact, it should), but its symbolic significance will always be mediated through more symbolic communication, chiefly language, and language cannot be a purely internal thing. We’re dealing with something a little more elusive than a situation in which one can walk up, kick a stone, and thus refute Kerwin forever. It’s a matter of whether we can reasonably give an act of symbolic communication a contingent, ontologically ungrounded, and equally symbolic label like “right-wing” without an audience to affirm its validity.

The question therefore is not so much, “If a tree falls in the woods and no one’s there to hear it, does it make a sound?” as it is, “If I invent a word for when a tree falls in the woods, and no one is there to hear it, is it a real word?” If I’m sure that I’ve created the perfect label to describe a tree falling in some woods, then great, but it doesn’t go anywhere or do anything until it’s put into regular usage. In order for language to be language, people need to know what the other person means. Similarly, in order for an artwork to have a certain meaning, there has to be an interpersonal understanding to establish that meaning, or else you’re left with a purely subjective, idiosyncratic takeaway. And although there may be some transcendent mystical value in having your own secret bījamantra that no one else knows besides you, the whole purpose of symbolic communication is otherwise to go places and do things — to acquire a shared understanding that everyone knows to be shared.

II.

For that reason, an artwork’s meaning is never purely intrinsic, and its meaning is established via some kind of agreed-upon, received interpretation. Without a receiving audience to make sense of it, it’s meaningless. And if it goes from one audience to another, its meaning will often change. Here. Let me show you how.

Example #1

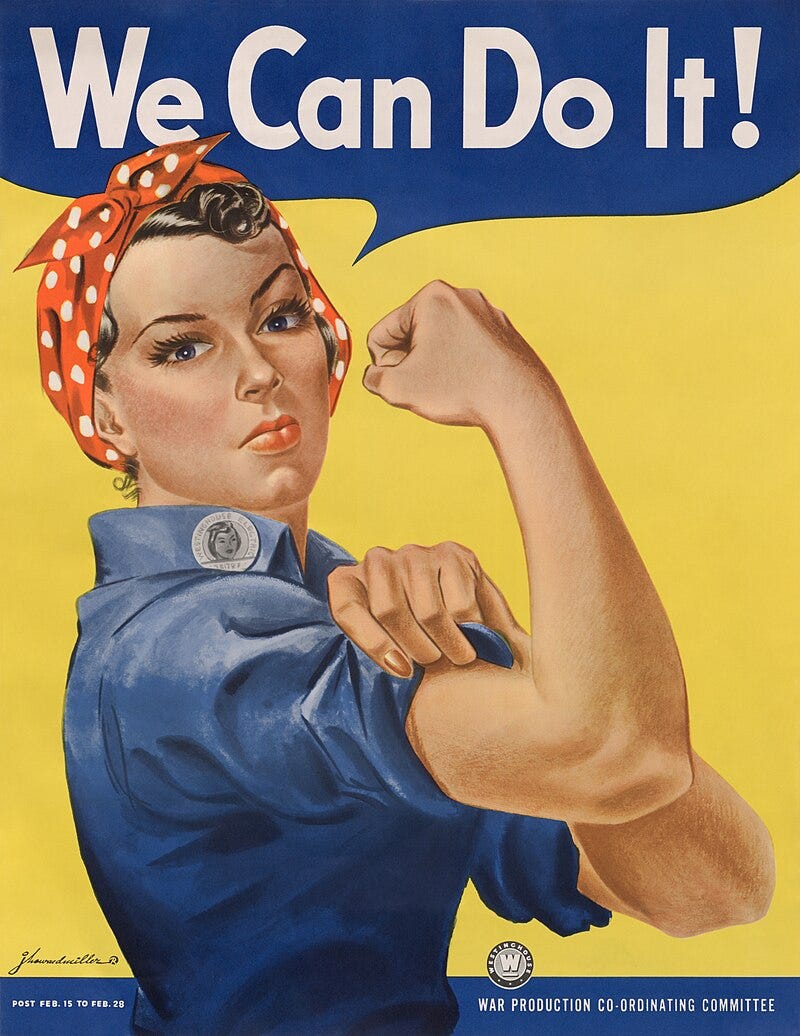

Maybe the most obvious example is J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It!” poster from 1943. During World War II, it wasn’t seen much or particularly well-known, and it was understood only as a straightforward call to boost worker morale by women working a specific job. It wasn’t a labor recruitment poster, and it wasn’t even commissioned by the U.S. Government. Rather, it was commissioned by Westinghouse Electric (you can see the logo at the bottom) for its labor management committee, since Westinghouse wanted to boost worker morale and avoid organized worker strikes. Whatever the poster was, it wasn’t about “empowerment.”

But then, in the 1980s, it was rediscovered by feminists who started co-opting it to promote women entering into male-dominated workplaces, competing with men more assertively than before. Shortly thereafter, it stood for Girl Power and became a widely commercialized symbol, a mainstay in American popular culture. So, was it a feminist image all along? No, not in any essential way — but then again, the question of whether feminists interpreted it “correctly” or not is pretty much irrelevant. The point is, whatever it was supposed to be at first, it became a feminist image, and that’s now what it is.1

So before we move on to the next example, take a second to imagine some poor old broad working at Westinghouse Electric in 1944 with wrinkles on her skin and sweat mounting on her brow, looking at that image plastered on the wall and thinking, “I know that in my heart of hearts, this poster is really about feminism and empowering women like me and my daughters to out-compete men!” Now, wouldn’t she feel like a bit of a doofus unless she could actually do something with that interpretation? It was only able to make sense once a specifically feminist infrastructure emerged to give that poster a specifically feminist reception.

But of course, that’s only a single image. There’s no narrative component. It’s not particularly textual. Right-wingers were able to do the same thing with the Pepe frog, so who cares, right? We’re supposed to be talking about more elaborate and complex things like films or novels. Surely, reception doesn’t determine a work’s significance in those types of art, right? The True Meaning is always there within it, waiting for just the right person to unlock it, no? Again — I think that such an attitude is just as naive.

Example #2

In Chaucer’s General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales, there are three priests: a friar, a summoner, and a pardoner. All three of them are corrupt and perverted weirdos. The summoner and the pardoner are homosexuals who bang each other — the summoner might even be a pedophile, since Chaucer remarks that children were afraid of him, although his sickly and diseased appearance might be enough to do the trick — and the friar has seduced plenty of women and paid dowries to get them all married off upon impregnation. There’s also a monk who spends more time hunting, wining, and dining than praying. The only time we get a truly devout sermon from a devout man is when it comes from the parson, a rustic parish priest at the lowest rung of the church’s hierarchy. Meanwhile, the narrator, a strange and elusive character in his own right, seems to be on the side of these pervert priests, but we also get the sense that he is merely playing dumb. Surely, The Canterbury Tales was written as an insurrectionary gesture — an anti-church satire to the core. Right? Well, it sure wasn’t taken that way when it was written. Even after the Lollard heretics became a big problem in the fifteenth century, after the church put up its defenses and imaginative literature went on a major decline for the next century-and-a-half, Chaucer’s work continued to be copied, while critics (and also boring poets) such as John Lydgate and Thomas Hoccleve dubbed him a master of style and wit, an exemplar of great English verse, indeed the father of English literature. When the Caxton press emerged, they printed Chaucer’s stuff.

How could Chaucer have not been a crypto-Lollard? More importantly: how could he have not been accused of such a thing? Only when you get a sense of the sociological facts of the church, along with what literature was like during Chaucer’s time, does any of this start to make sense. The Catholic church didn’t have any competing alternative institutions at the time Chaucer was writing, and so it could afford to brook internal criticism rather comfortably. Additionally, what we find in Chaucer’s depictions of priests was already there in earlier estates satires and French fabliaux, and we additionally find the kinds of zany situations that they got involved in all the way back into late classical satire (see Apuleius’s Golden Ass, which contains a section that Boccaccio adapted in his Decameron). Chaucer’s mostly educated audience was already used to seeing these literary commonplaces and topoi in Latin, and so, with a humble and devout retraction at the very end of his works, Chaucer could evade accusations of heresy.

Nevertheless, today, when Chaucer is taught to high school or college students, you’ll often see them giving interpretations like this essay, in which he is portrayed essentially as a church reformer on par with Martin Luther. It’s hard to escape that same conclusion with the hindsight of modernity, but it’s historically mistaken all the same. And yet… although it’s historically incorrect, there’s nothing essentially wrong with saying that the Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale, to take the most extreme example, is an affront to the Catholic church and a blow to the legitimacy of church authorities. It’s an interpretation that modern audiences cannot help but take from the text, and there’s nothing wrong with stating the obvious, namely that Chaucer’s work stands as a sign of the corruption of the priesthood that would later prompt rebellions like those of the Lollards, Jan Hus, and later the Lutheran reformation. This is a significance that just wasn’t there at the time, but then again, why should the circumstances of history shackle the work’s significance to a previously agreed-upon meaning?2

Example #3

The late twelfth-century Latin treatise on love, De Amore by Andreas Capellanus, is an even better example of what I’m discussing, though, because its meaning actually changed in the eyes of the church itself, the most official arbiters of a text’s significance. This curious little document, which I discuss extensively in probably my most underrated post, was written as a guide to understanding fin‘amor, or what’s commonly called “courtly love,” and it says plenty of things that go directly against the teachings of the church. For instance, it completely excuses marital infidelity, arguing that love is too powerful to be held back by the bonds of marriage. For the first two thirds of the text, it gives the reader sample dialogues of courtly love wooing, rules about courtly love, and historical examples of countesses and aristocrats who have practiced courtly love, all without the slightest hint of judgment. But then, in Book III, Andreas pivots sharply and issues a stark repudiation of love alongside a bitter invective against women. Quite the turn.

For a good while, twentieth century literary critics (including C.S. Lewis) felt that the first two books were written with a sincere intent, but the third book was just written so that Andreas could cover his ass. But then, the scholarly consensus shifted to say that the first two books were probably written ironically, while the third book was sincere. The later consensus is more convincing. What’s most interesting about De Amore, however, is that although it was probably not written with a sincere intent (at least for the first two books and perhaps even the third), it wasn’t exactly a work of gut-busting, knee-slapping satire, either. There are ideas within it that are conceptually funny, but the execution isn’t funny at all, and so whatever irony it contains isn’t exactly there for laughs. To this day, there is no clear scholarly consensus on what this book was meant to accomplish or why it was written. It is pretty baffling.

But whatever its purpose may have been, it was eventually condemned by the church in 1277, almost a hundred years after it had been written. In the official document condemning it, Bishop Étienne Tempier subjected 219 strands of Aristotelianism, occultism, and other paganism-tinged ideas and teachings to intense criticism, claiming that they should all result in immediate excommunication. The only two specific examples he provided, however, were a book on geomancy and De Amore. We might take that document as evidence that Andreas’s promotion of fin’amor had been sincere all along, but then again, why did it take so long for the church to realize, “Oh, gee, I just noticed this is blasphemous”? The German scholar Alfred Karnein offers the most convincing explanation: by that point, De Amore was starting to be translated into the vernacular, and this was a problem. As a work of Latin writing, its educated audience could see it as a benign thought experiment of some sort without concluding that it’s in fact sincerely encouraging adultery. But once the text transcended the boundary between the higher and lower registers of discourse, then its meaning had to change: it had to go from being merely interesting to outright condemnable. What other choice was there? The delayed reaction of the church makes it clear: the book’s meaning changed, not because of what was actually in it, but because of the significance drawn from its pages by an entirely new audience.

III.

Simply by having its audience grow and become a little dumber, the De Amore thus turned into a stick of dynamite. And this is by no means an isolated case, either, since this sort of thing happens often today. When a right-wing audience “memes” some film or work of art into becoming conventionally right-wing, the effect is structurally similar. If there are unsupervised interpretations going on, ones that stray from the authoritative exegesis, then it freaks people out in the almost exclusively left-liberal media industry, and so they respond. The difference, however, is that they cannot issue decrees formally censuring a work as the Catholic church once did during the medieval period, because we live in a nominally liberal country. Although things may be changing, we’re still ruled by foxes, not lions. So instead, they have to resort to more curious maneuverings.

Consider the way right-wingers have semi-recently adopted Christian Bale’s performance as Patrick Bateman from American Psycho (2000) as a symbol for themselves. In that situation, you’ve got a group of young men with their hands quite far from the levers of official-cultural-narrative-construction, and they decided it would be funny to co-opt the image of Bateman, a figure in a film by a feminist director who was trying her best to produce anti-corporate satire in the same manner as the original novel. These memes, showing brazen disregard for the film’s intent, have freaked people out a little bit, with the mainstream media going out of its way to reassure everyone that the film is on the right side of history, and so was the director, and that Bret Easton Ellis (the original novel’s author) was criticizing heteronormativity from a gay man’s perspective. But the memes have continued undeterred, and these corrections have fallen upon deaf ears. Clearly, a different strategy to stop these interpretations must be implemented. As I write this, I don’t think it’s too ridiculous to wonder aloud if the film industry is now trying to stop the meme-ing of Patrick Bateman altogether by getting ultra-queer director Luca Guadagnino to direct a new adaptation of Ellis’s novel — one that, judging by Guadaginino’s other films, will be far too gay for any self-respecting heterosexual young man to meme.

It feels bizarre to even type out those words, but yes, this sort of thing is happening strategically nowadays, and people in the culture industry do think about this stuff. For instance, when director Todd Phillips’s Joker (2019) was co-opted by various right-wingers as a personal symbol of their own frustrations, Phillips sort of lost his mind and directed a sequel, Joker: Folie à Deux (2024), which was more or less designed to annoy the fans of the first movie. He was clearly upset that various right-wingers and edgy online personalities had been using Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker character as a way to ventilate their frustrations and indulge in their repressed desires to transgress taboos, with the incel community playing a particularly outsized role, and so he decided to make a sequel that relitigates the events of the first movie, removes the possibility for any romantic interpretations of what happened, and has Joker die in the end. The film, in a word, sucked. It was nominated for seven Golden Raspberry awards, and it won two. But was it a total failure? Well, everyone seems to agree that it was awful, but it did barely break even in net earnings, and I haven’t seen any right-wing-coded Joker memes lately… so, really, who’s to say?

Turning back to the question of Force Majeure, the film that sparked this whole discussion, there we’ve got something that was released worldwide to a sophisticated, educated urban audience with left-wing politics by default. And if you’ve traveled in those circles, you’ll know that you can always get away with saying slightly edgy things as long as you present yourself as left-wing and give your peers the occasional (yet subtle) reassurance that you’re on their side. Many left-wingers do precisely this — it’s actually what the entire “dirtbag left” style was predicated upon during the mid-to-late-2010s. It helped left-wing guys in their mid-20s get laid because it gave them the permission needed to transgress nonsensical social-justice taboos (the kind of transgression that chicks dig, despite saying otherwise) while ultimately getting to be the guy who nonetheless possesses a heart of gold; the guy who stays focused on what truly matters, namely the cause of equality (sweet, sweet equality). Although Force Majeure is far better than something as paltry as a “dirtbag left” movie, it was nevertheless received along the same lines: it conveys uncomfortable truths without registering a complete and total break from the commitments of civilized left-liberal society. And more importantly, it has a national literary tradition behind it, one that exhibits its same dark and uncomfortable ironies, and this makes it part of a cultural continuity, just as the Canterbury Tales had its own array of literary predecessors. As one commentator on social media pointed out, it’s really a Strindbergian film first and foremost, not really “left-wing” nor “right-wing.”

Now, imagine if Force Majeure had gotten a significant and vocal right-wing following shortly after its release. This is actually a scenario that I’m curious about, because I don’t have a clear idea of what would happen if this occurred with a smaller-budget feature. Imagine that instead of merely meme-ing it for some cheap laughs, you had an intelligent and sophisticated self-consciously right-wing cultural journal and maybe a constellation of surrounding podcasts that all gave it rave reviews (or at least debates its merits), observed its clearly reactionary (and true) implications regarding sex roles, and brought them into relief. I mean, really rubbed it in, you know? And not in a lame and goofy way where the writer goes, “Hey everyone! This is /ourfilm/! It’s based and red-pilled! A-hyuk!” No, I mean in a way that actually takes it seriously, discusses it on its own terms, contextualizes it as a part of Swedish literary and theatrical/cinematic history, and still comes away with the conclusion, “Yes, this is a good film with a distinctly reactionary subtext.” This, I think, would do something interesting, and only in a situation like that could the film really be part of a right-wing canon of cinema.

Of course, such a gesture could also cripple independent cinema and put it into a defensive position of puritanical self-censorship, that is, if it worked all too well. The left has been cannibalizing itself quite a bit lately as they regularly police each other for clues and slip-ups that might “out” their peers as closeted reactionaries. Maybe the mere knowledge that independent art productions are being viewed and patronized by The Bad Guys would result in the cessation of good, non-propagandistic independent art entirely! But this should be a risk that people are willing to take, since alternatively, it might also signal to others that there is an audience of people who are perfectly welcoming toward off-the-grid ideas, thus encouraging investors and patrons. This scenario, by the way, is the kind of thing I’m trying to get at when I talk about the need for a right-wing infrastructure of cultural reception. An audience determines the meaning of a text or an artwork, and so a substantial right-wing cultural presence absolutely requires a network of critics and commentators ready to receive a work, discuss it in detail, and if it has some interesting themes, point them out and rub it in. That is: debase whatever high-minded sociopolitical pieties that people want to attribute to it by simply observing what’s there.

And look. Even though he disagreed with me, Yarvin contributed to exactly the kind of thing I want more of by simply saying, “Force Majeure is based,” thus prompting some of the people in his replies to agree, “Yes, I agree, it is based and/or red-pilled, as are Östlund’s other films.” Personally, I still don’t think it can be properly called a “right-wing” movie… not yet, anyway. But then again, didn’t it feel liberating to just, I don’t know, discuss it? To actually acknowledge that it’s a thing that’s there? I had only ever seen right-wingers mention it once beforehand. All questions of idealism aside, for the unconvinced, how about this: prove me wrong by partaking in the kind of infrastructure for cultural reception that I’m describing.

See James Kimble and Lester Olson’s essay “Visual Rhetoric Representing Rosie the Riveter: Myth and Misconception in J. Howard Miller's "We Can Do It!" Poster” (2006) for more details. It also includes some pretty funny and decidedly non-feminist images by the same artist.

And this is to say nothing of Pasolini’s 1972 film adaptation, which he considered among his “most ideological” works, and which completely reinterpreted the Canterbury Tales’ significance as a morality-free celebration of bodily pleasure — saving the church from criticism, paradoxically by morally excusing the act of illicit sex altogether. Again, his understanding of the text is not wrong. You might say “not even wrong,” but still… not wrong!

Bret Easton Ellis may be gay, but he's a controversial figure on the left. Not quite Milo levels, but he has that Milo spirit of disagreeable, anti-establishment flamboyance. He wrote a book called "White" which you can imagine pushed all the wrong buttons, because it was only a little self-hating.

I'd say the body of all his work is ripe for New Right/Dissident Right aesthetics, if you can swallow the hedonism. His early novels ( Less than Zero, Rules of Attraction, Glamourama, American Psycho) are all drug-fueled 1980s extravaganzas of the ultra-rich partying together that can be read as critiques of the excess, but also romanticizing a moment in time of American pop culture. There's a huge nostalgic pull I felt for cocaine-fueled synth-pop orgies, despite not being alive then, and I see some similar aesthetic sensibilities among some other parts of the DR (eg "fashwave" music).

I used to rub it in with church icon stones or something l I l I l I like this in England with wax or something like this I dont remember exactly what it was called I did this with my mother