Note: What follows is Part 1 of a multi-part series. To access Part 2, click here. For Part 3, click here. Part 4, here. Part 5, here.

I. Introduction - The Graveyard of Discredited Research

Starting a little over a decade ago, a number of highly influential social psychology experiments have been invalidated, with researchers demonstrating that they were planned, conducted, and interpreted according more to ideological bias than disinterested scientific inquiry. One was the infamous Milgram shock test experiments, which supposedly showed that most human beings will, when placed in an official and proper-seeming atmosphere, electrically shock a guy using fatal levels of voltage merely because an authority figure has instructed them to do so. That’s a disturbing thought. But the writer and psychologist Gina Perry showed in 2013 that the results weren’t nearly so straightforward as the researcher Stanley Milgram made them seem, because of the 65% who consented to keep shocking the guy (who was just pretending to be shocked), quite a few suspected correctly that the shocks weren’t real and the guy was simply acting. The upshot to Milgram’s research should have been that some people will keep shocking a guy… but we really don’t know how many, or why.

Later on in 2019, the same author Gina Perry debunked the “Robber’s Cave” experiment conducted by Muzafer Sherif. That particular study purported to show that groups of boys will become hostile towards each other over contested resources, but they will then cooperate when they’re presented with an outgroup-generated problem that requires them to work together. Sherif did this by creating a summer camp, having some unsuspecting boys sign up for it, and then he put them in some contrived situations that would test the hypothesis. As it happens, however, Sherif and his team were manipulating the boys and trying to goad them on to fight each other, which puts the results about their behaviors as well as the nice cooperative ending into question. The researcher and his team were simply way too involved with the research subjects.

Here’s another example, and it’s an important one. The Stanford Prison Experiment conducted by Philip Zimbardo has been exposed as a complete and utter hoax — an utterly shameless display of academic fraudulence that never should have been taken seriously for even one second. Zimbardo insisted that he had demonstrated that arbitrarily giving some people the authority of prison guards while endowing others with the helplessness of prisoners will make the guards absolutely sadistic and deranged towards the prisoners — simply by dint of the arbitrary role selection. He did this by recruiting some bright, mentally stable Stanford students, randomly giving one half of them a “guard” role and the other half a “prisoner” role, and creating a realistic prison simulation in which they’d interact. The experiment even included a simulated arrest scenario and an ersatz holding facility. According to his account, he had to stop the study after six days (it was meant to last two weeks) because the guards were simply too abusive, and the prisoners were being so badly mistreated that they were having mental breakdowns. Zimbardo had to let some prisoners go before the experiment had even ended. Things, in other words, had gotten way out of hand. It makes for a great story.

But unfortunately, Zimbardo had determined the results in advance, writing the conclusions down before he had even begun the experiment. He more or less instructed the guards on how to behave, he repeatedly guided their harsh behavior throughout the study, and some of the prisoners later admitted that they acted more hysterical than they were in order to be released early even while knowing the situation was artificial (one, in fact, was confused to find that he had been granted release early with no explanation given, though Zimbardo’s account presents him as also having been too mentally distressed to continue). The whole thing is thus better understood as an elaborate work of experimental improv theater. Now, apparently there was some real psychological damage done to two participants who did exhibit legitimate signs of a nervous breakdown, which is pretty messed up. But if you’re nudging your guards to behave like assholes, and the guards themselves aren’t sure of how genuinely perturbed the prisoners are, then you can’t conclude anything about human behavior from such a study. It’s complete bunk.

All of these social psychology confutations (and there are others I didn’t mention) demonstrate qualitatively, on the one hand, what the replication crisis has shown quantitatively on the other: namely, that psychology is not a real science. At least, that is, not according to its own standards. These debunkings can also be understood as one minor benefit of academia’s oversaturation from the last few decades. It is now considered normal to write academic biographies of other academics, conduct historical research about earlier historical research, and to do evaluative book-length studies on earlier scientific studies. This means that much of the majorly influential psychology research produced from the 1950s through the 1970s — the stuff psychology and sociology students will typically encounter in beginner’s textbooks and introductory courses — can finally be exposed as the ideologically-driven slop that it always was, with more people getting graduate degrees and learning the basics of research than ever before. It’s unfortunate that this development has had to rest on a needlessly bloated university infrastructure, which has produced a far greater mass of garbage than good scholarship could ever hope to keep up with. But, hey. A win is a win.

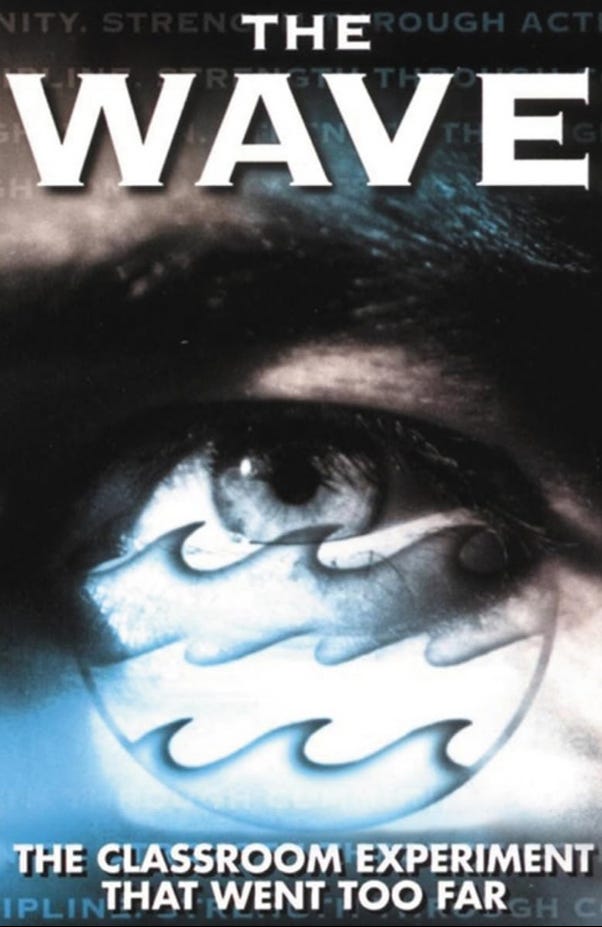

I’d like to contribute to these confutations and debunkings with one of my own. It’s not nearly as professional or as large in scope, since the “experiment” I’m debunking was never recognized as legitimate by the broader scientific community in the first place. But its illegitimacy didn’t stop it from being thrown into social psychology textbooks for college students and lesson plans for high schoolers; it didn’t stop its “researcher” from using his story about it as the basis of a career; and it certainly didn’t stop the culture industry from adapting it into numerous media productions ranging from a) a young adult novel to b) an ABC After School Special to c) a stage play to d) a theatrical film to e) a six-episode Netflix TV series… and more! The experiment I’m talking about is “The Third Wave,” conducted by Ron Jones, which took place at Cubberley High School in Palo Alto, California, 1967.

II. On Modern Metapolitical Folklore

This particular pseudo-experiment has been interesting to me for quite some time, since the many retellings it has spawned all collectively constitute an example of metapolitical folklore in the electronic age. One of this blog’s major contentions is that the age of electronic media has brought modern society back into a kind of folkloric state of information transmission — something that resides somewhere between literacy and orality. The closest historical approximation to how ideas travel would be the time period following the so-called Axial Age but prior to the invention of the printing press. In that time, an ur-text or canon of writings would form the basis of a society, and stories would emerge that generally fit into its underpinnings: its metaphysics, its ethical contours, its codes of honor. These stories might change around in structure and detail, but they ultimately remained anchored to these textually derived ideals. Think, for instance, of the medieval hagiographies, which constituted much of the vernacular literature across Europe, rivaled only by chivalric romance. The stories of heroic saints (like St. George the dragon-slayer) would be told from person to person, and thus they could change quite a bit and be written down differently in various places. But what gave all the versions of this story their source of meaning was ultimately the Bible.

I won’t dwell on this idea for too long, but basically, our media environment has restored the logically rudderless and agglomerative thought processes of pre-literate tribes and bands while also preserving the tendency for abstract, disincarnate considerations (e.g. morality, ideology, maybe even metaphysics) to form the basis of tribal identity. This means that some information, typically taking the form of an instructive story, will travel much like folklore does but with big-budget media presentations sometimes marking new versions of the story from which oral accounts can deviate further. In preliterate times, folklore was largely amoral and only contained the seeds of metaphysics, but today’s folklore is often fueled by a kind of ideological zeal that one only finds in literate communities.

This phenomenon I’m describing is not necessarily internet-based, either, though the internet has exaggerated the tendency in question (think of something like QAnon). The example I’ve chosen serves to demonstrate that this sort of process was going on before internet usage was common. It’s also necessary to note that what I’m describing isn’t simply a re-adaptation of an old folk tale done to produce timely propaganda, like Tex Avery’s Blitz Wolf using the Three Little Pigs to encourage citizens to buy war bonds. That sort of thing (which actually was quite common in Soviet Russia) is described by historians as pseudo-folklore, since it never was transmitted organically from person to person in an impactful way. What I’m describing typically involves original stories with some resemblance to an event that actually happened, and with each retelling, the events grew increasingly distorted from the original account even while its moral message has stayed consistent. At the end of my study, I’ll try to venture a few rules of thumb for how modern metapolitical folklore functions. But for a couple weeks, you’ll have to bear with me as I pick apart a fairly ridiculous story that people genuinely felt (and still feel) conveys a legitimate psychological and/or moral truth.

III. The Co-Evolution Quarterly

I’ll soon explain what happened according to Ron Jones’s account from 1976 (and note the nine-year gap between the event and its recollection, which we’ll discuss later), but first, let me quickly say something about the magazine in which Jones’s essay was originally printed. The original piece that Jones wrote about his experiment was not published in an academic journal but rather in a techno-optimist DIY hippie-dippy magazine called Co-Evolution Quarterly (originally The Whole Earth Catalog) founded by counter-culture figure Stewart Brand and based in Sausalito, CA — right in the Silicon Valley area, and right near Palo Alto where Jones lived and conducted his experiment. According to Wired magazine, it was a “proto-blog—a collection of reviews, how-to guides, and primers on anarchic libertarianism printed onto densely packed pages,” and it had a strong impact on the ethos of Silicon Valley (Steve Jobs actually referenced The Whole Earth Catalog in his 2005 commencement speech at Stanford University). Jones originally titled his essay “Take as Directed,” and the exact issue in which it appears can be found here.

Looking through the entire periodical, one can see that it’s typical of what you’d expect from a left-wing 1970s counter-culture magazine. It has lots of underground comics all over its pages, a poetry section, excerpts of an interview with Joni Mitchell, and plenty of DIY material for hippies who want to build stuff and get “back to the land.” Amusingly, there’s a hostile review of E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology (“This book is too ethnocentric and too anthropocentric. It is also too ego-centric”). And there’s also actually a pretty good rant about the arbitrariness of the metric system, with which I totally agree — though, of course, it ends with a cowardly display of submission to the international community, stating that America should ditch the imperial system just to make things more convenient.

I bring all this up mostly to point out that Jones’s work didn’t get attention on account of his procedural diligence or exhaustive research or anything like that, but rather through the cultural influence that this magazine had. Perhaps Jones had social ties to its founder Stewart Brand, who wrote a brief note at the beginning of his piece — though perhaps not, because Brand misidentifies the year at which the experiment took place. But given that the magazine was directed to hippies (a largely upper-middle class movement) and also “back to the land types” (equally an elite phenomenon in virtually all its instantiations, from Robert Penn Warren’s Southern Agrarian movement to today’s homesteaders, who also have close ties to Silicon Valley), it’s fairly safe to say that Jones was communicating to an elite, upper-middle class, culturally influential audience, and that’s what opened the doors for him. That, and the fact that he was delivering a message that everyone wanted to hear.

Now, onto the experiment.

IV. The Third Wave Experiment, Day One: Strength Through Discipline

It started when Jones was trying to explain to his 10th grade World History students the importance of Nazi Germany, and one of the students asked him how the German populace could claim ignorance of the slaughter of the Jewish people. How could all of the townspeople claim that they knew nothing about the concentration camps and all of the human carnage within? Jones couldn’t think of an answer to the question, so he decided to conduct a social experiment to try and explore that problem, but he wouldn’t tell the students what its purpose would be until the very end. It began on Monday and lasted five days — a full school week.

I’ll quote liberally from Jones’s account, which can be found in a more digestible form here (though the web site seems to have scanned it from a print source, resulting in some typos). I highly recommend reading the whole thing just to get a sense of what we’re dealing with, but I’ll go over the essential information.

On Monday, I introduced my sophomore history students to one of the experiences that characterized Nazi Germany. Discipline. I lectured about the beauty of discipline. How an athlete feels having worked hard and regularly to be successful at a sport. How a ballet dancer or painter works hard to perfect a movement. The dedicated patience of a scientist in pursuit of an idea. It’s discipline. That self training. Control. The power of the will. The exchange of physical hardships for superior mental and physical facilities. The ultimate triumph.

To experience the power of discipline, I invited, no I commanded the class to exercise and use a new seating posture. I described how proper sitting posture assists mandatory concentration and strengthens the will. In fact I instructed the class in a sitting posture. This posture started with feet flat on the floor, hands placed flat across the small of the back to force a straight alignment of the spine. “There can’t you breath more easily? You’re more alert. Don’t you feel better?”

The whole essay is written in this young-adult fiction style, by the way: sparsely punctuated and replete with sentence fragments used for dramatic effect. Jones continues on, explaining that for the first half of the class, he did various drills in which the students would practice entering the classroom, sitting down, and entering the specific posture he instructed them to assume. He also drilled them to concentrate on the accuracy and correctness of their postures. Lastly, he did something called “noise drills,” which were meant to show that talking out of turn creates a distraction.

For the second half of the class, Jones says that he introduced some new rules, which go as follows:

Students must be sitting in class at the attention position before the late bell.

All students must carry pencils and paper for note taking.

When asking or answering questions, a student must stand at the side of their desk.

The first word given in answering or asking a question is “Mr. Jones.”

He then had the students do some silent reading, and he instructed the students to engage with each other in a question and answer session, requesting that answers be given in three words or less. He was astonished at the results.

As for my part in this exercise, I had nothing but questions. Why hadn’t I thought of this technique before? Students seemed intent on the assignment and displayed accurate recitation of facts and concepts. They even seemed to be asking better questions and treating each other with more compassion. How could this be? Here I was enacting an authoritarian learning environment and it seemed very productive. I now began to ponder not just how far this class could be pushed but how much I would change my basic beliefs toward an open classroom and self directed learning. Was all my belief in Carl Rogers to shrivel and die? Where was this experiment leading?

I suppose that for a left-wing teacher during this time, nothing would be more disturbing than realizing after just a single day of implementation that a non-progressive education model is actually pretty effective.

V. Days Two and Three: Strength Through Community and Action (respectively)

On the second day, Jones walked into the classroom to find the students eerily disciplined before he had even entered. Everyone was

sitting in silence at the attention position. Some of their faces were relaxed with smiles that come from pleasing the teacher. But most of the students looked straight ahead in earnest concentration. Neck muscles rigid. No sign of a smile or a thought or even a question. Every fibre strained to perform the deed.

That’s a little bizarre, but OK. Anyways, he writes down “STRENGTH THROUGH COMMUNITY” onto the chalkboard, and then spends most of the class lecturing about the importance of community. He makes the class recite the mantra, “Strength through discipline. Strength through community” in various ways, with different subdivisions of the class chanting it at a time until everyone does it in unison. Then, he invents a hand signal called “The Third Wave Salute,” in which you cup your right hand and throw it up near your right shoulder. Jones explains that he created the name “The Third Wave” because according to beach lore, waves occur in chains of three with the third being the biggest, and the cupped hand gesture was meant to resemble a wave beginning to crash. He tells the students that they must always greet each other outside of class using this salute, and the students agree.

It is hard to believe that his students wouldn’t have immediately seen the similarity between a name like “the Third Wave” and the Third Reich, which they were learning about right at that time.

On day three, Wednesday, Jones decided to introduce the idea of “strength through action.” Now, according to Jones, 43 students attended his class that day instead of the standard 30, since thirteen decided to skip their other classes. Jones gave everyone in the class “membership cards,” and he marked three of them with red X’s, which indicated that they had a special responsibility to report other classmates to him who were not following the class rules. He then lectured a little bit about the importance of using discipline and community to create action, and then presented the students with an assignment (emphases in original).

To allow students the experience of direct action I gave each individual a specific verbal assignment. “It’s your task to design a Third Wave Banner. You are responsible for stopping any student that is not a Third Wave member from entering this room. I want you to remember and be able to recite by tomorrow the name and address of every Third Wave Member. You are assigned the problem of training and convincing at least twenty children in the adjacent elementary school that our sitting posture is necessary for better learning. It’s your job to read this pamphlet and report its entire content to the class before the period ends. I want each of you to give me the name and address of one reliable friend that you think might want to join the Third Wave.” . . .

To conclude the session on direct action, I instructed students in a simple procedure for initiating new members. It went like this. A new member had only to be recommended by an existing member and issued a card by me. Upon receiving this card the new member had to demonstrate knowledge of our rules and pledge obedience to them. My announcement unleashed a fervor.

According to Jones, the other teachers, the librarian, and even the principal were all supportive of his experiment. He also found that twenty students came to him and snitched on other students who were failing to follow all of the rules instead of the three he entrusted with the task.

Importantly, he found that three intelligent girls from the class later told their parents about Jones’s experiment, because they did not like what was going on. According to Jones, these girls merely “watched the activities and participated in a mechanical fashion.”

I’ll quote once more from Jones, because he provides a detail worth considering briefly:

In telling their parents of the experiment [the girls] set up a brief chain of events. The rabbi for one of the parents called me at home. He was polite and condescending. I told him we were merely studying the German personality. He seemed delighted and told me not to worry. He would talk to the parents and calm their concern. In concluding this conversation I envisioned similar conversations throughout history in which the clergy accepted and apologized for untenable conditions. If only he would have raged in anger or simply investigated the situation I could point the students to an example of righteous rebellion. But no. The rabbi became a part of the experiment. In remaining ignorant of the oppression in the experiment he became an accomplice and advocate.

There are two key takeaways from this last tidbit. First, Jones is assuming that the rabbi couldn’t have possibly understood what he was actually doing, as if “the German personality” he mentioned was just taken as some benignity. If this part of the story isn’t wholly fabricated, it sounds like the rabbi knew exactly what Jones was doing and appreciated what he perceived to be the wisdom in it. It’s worth bearing in mind that progressive education had been around for decades. John Dewey wrote as early as 1916 about the value of immersing students into lifelike situations because he saw experience and reflection as primarily cognitive processes that strengthen conceptual understanding. It is hard to believe that this rabbi wouldn’t have immediately grasped that the experiment was about simulating the Nazi regime and understood the pedagogical theory behind it. The second takeaway is that Jones specifically indicates that there were no examples of righteous rebellion. This is a lie, and we’ll discuss that later.

Oh, and Jones also mentions that a slow kid from the class volunteered to be his personal bodyguard.

VI. Day Four: Strength Through Pride (the Nazi kind, of course, not the good kind with like the rainbows and stuff)

On Thursday, Jones was disturbed by what his experiment was doing with the students, and so he decided that he had to conclude it somehow, but he didn’t know the way, since according to his account he was freely improvising everything. He also includes this interesting tidbit:

Things were already getting out of control. Wednesday evening someone had broken into the room and ransacked the place. I later found out it was the father of one of the students. He was a retired air force colonel who had spent time in a German prisoner of war camp. Upon hearing of our activity he simply lost control Late in the evening he broke into the room and tore it apart. I found him that morning propped up against the classroom door. He told me about his friends that had been killed in Germany. He was holding on to me and shaking. In staccato words he pleaded that I understand and help him get home. I called his wife and with the help of a neighbor walked him home.

Note that just a few paragraphs before this passage, Jones complains that he lacked any examples of righteous rebellion to show the students. On Wednesday night, he supposedly talked to the rabbi, and on the same night, a student’s parent supposedly tore up the classroom, so that would seem to constitute an example of righteous rebellion. Even in his own account, Jones fails to remain consistent.

Now, Jones claims that on Thursday, his class ballooned up to 80 students: “The only thing that allowed them all to fit was the enforced discipline of sitting in silence at attention.” This must have been quite a large classroom. Perhaps it was a lecture hall that was meant to be mostly vacant. In any case, Jones told the class about “strength through pride.” He began with some prefatory remarks about pride, and then told them this:

The Third Wave isn’t just an experiment or classroom activity. It’s far more important than that. The Third Wave is a nationwide program to find students who are willing to fight for political change in this country. That’s right. This activity we have been doing has been practice for the real thing. Across the country teachers like myself have been recruiting and training a youth brigade capable of showing the nation a better society through discipline, community, pride, and action. If we can change the way that school is run, we can change the way that factories, stores, universities and all the other institutions are run. You are a selected group of young people chosen to help in this cause. If you will stand up and display what you have learned in the past four days. . . we can change the destiny of this nation. We can bring it a new sense of order, community, pride and action. A new purpose. Everything rests with you and your willingness to take a stand.

He then dismissed the three girls who weren’t enthusiastic about The Third Wave, and banished them to the library, telling them that they weren’t allowed to attend class on Friday.

Afterwards, he told the class that on Friday, there would be a big Third Wave rally at school in the small auditorium at 12:00 noon. This rally would occur simultaneously alongside 1,000 other rallies held by other Third Wave youth groups across the country, and “a national candidate for President” would announce to everyone the formation of a Third Wave Youth Program. He also told them that the press had been invited to record the event. He assures the reader that “no one laughed.”

VII. Day Five: Strength Through… Uh… Understanding…?

On Friday, it was finally time for the big rally, which he had only planned supposedly just the day before. Jones tells us that several of his friends were there posing as members of the press, and Third Wave banners had been hung up around the auditorium (presumably these are the banners he instructed his class to make on Wednesday; Jones doesn’t explain where they came from). He also tells the reader that over 200 of the seats had been filled up, and it contained various groups of students:

There were the athletes, the social prominents, the student leaders, the loners, the group of kids that always left school early, the bikers, the pseudo hip, a few representatives of the school’s dadaist click, and some of the students that hung out at the laundromat.

All of them, according to Jones, had their eyes fixed on a TV set that he had placed at the front, which is where the national Third Wave Youth Movement leader would have made his announcement.

But this was not to be. Jones turned on the TV, and it just showed a blank white signal screen for two minutes while the students sat impatiently. Eventually, one of them asked aloud, “There isn’t any leader is there?” while the other students’ faces held expressions of disbelief. Then Jones went up to the class, turned off the TV, and gave them this speech:

Listen closely, I have something important to tell you. Sit down. There is no leader! There is no such thing as a national youth movement called the Third Wave. You have been used. Manipulated. Shoved by your own desires into the place you now find yourself. You are no better or worse than the German Nazis we have been studying.

You thought that you were the elect. That you were better than those outside this room. You bargained your freedom for the comfort of discipline and superiority. You chose to accept that group’s will and the big lie over your own conviction. Oh, you think to yourself that you were just going along for the fun. That you could extricate yourself at any moment. But where were you heading? How far would you have gone? Let me show you your future.

And then at that point, he turned on the auditorium’s rear projector, which cast a much larger image over the stage, and what did it depict? Why, the Nazis! Nazis, Nazis, everywhere! Nazis as far as the eye can see! Or, as Jones retells it,

In ghostly images the history of the Third Reich paraded into the room. The discipline. The march of super race [sic]. The big lie. Arrogance, violence, terror. People being pushed into vans. The visual stench of death camps. Faces without eyes. The trials. The plea of ignorance. I was only doing my job. My job. As abruptly as it started the film froze to a halt on a single written frame. “Everyone must accept the blame. No one can claim that they didn’t in some way take part.”

He then proceeds to lecture the students about he tricked them all into becoming Nazis for a few paragraphs (I’ll spare you the ridiculousness of his argument). He further tells them that just like the Germans never admitted they knew Jews were being tortured in camps, they’ll never admit to having attended the Third Wave rally: “You will keep this day and this rally a secret. It’s a secret I shall share with you.”

The slow kid who volunteered to be his bodyguard starts crying, and Jones tells him, “It’s over. It’s all right” as they embrace. Some other students start crying as well while everyone exits the auditorium. The end.

There’s much to say about Ron Jones’s story that can be contradicted by external evidence, and we’ll get there, I assure you. But for now, I can’t help but note another internal inconsistency in his own writing. He begins the entire essay by talking about a student named Steve Cognilio who recognizes him, gives him a Third Wave salute, and the first thing he says is, “Mr. Jones do you remember the Third Wave?” which prompts all the memories to come flooding back into Jones’s consciousness. But he ends the essay with these words:

As predicted we […] shared a deep secret. In the four years I taught at Cubberley High School no one ever admitted to attending the Third Wave Rally. Oh, we talked and studied our actions intently. But the rally itself. No. It was something we all wanted to forget.

Apparently, the event was so traumatic that everyone wanted to forget it… except, of course, this student who immediately wants to talk about it, apparently quite nonchalantly, upon seeing his former teacher.

Alright, that’s enough for now. Next week, we’ll explore the writings of an earlier blogger who completely demolished Ron Jones’s story and got real students from that class to message him with their accounts of what actually happened. And we’ll also talk about how some Wikipedia editors conspired to bury his research. Stay tuned.

Edit 7/24/2024: I removed a sentence accusing Jones of lying about a certain detail, because I realized it may have been true, but in reference to only one of his three classes that he tried the experiment with.