"The Third Wave" Wave, pt. 4: Three Adaptations

Narrative drift from essay to TV to novel to film (with plenty of spoilers, not that you care)

Note: this post is the fourth part of a series on the Third Wave Experiment as an example of modern metapolitical folklore. For Part 1, click here. For Part 2, click here. For Part 3, click here. For Part 5, here.

Introduction

Every adaptation, when you think about it, can be taken as both an homage and a critique. From one perspective, the creator in charge of it has been moved enough by the source material to keep its legacy alive. But from another, he must also implement changes that inherently tell us something about where the material has faltered, or where it might no longer resonate. This is a principle that we should keep in mind when examining the series of adaptations that Ron Jones’s influential essay “Take as Directed” from the Co-Evolution Quarterly (1976) spawned. In the last two parts of this series, I’ve done my best to give the most realistic possible assessment of what actually happened in Palo Alto back in 1967 that influenced Ron Jones to write what he did, researching as many perspectives as I could hope to find, and determining how to resolve the logical inconsistencies and internal contradictions in Jones’s own writing.

From what I can tell, the actual story of “The Third Wave” is fairly amusing if interpreted properly. It would make for a good, lighthearted, slice-of-life tale about a minor series of events that took place in an idealistic but impractical high school in an upper-middle-class progressive California town. It would contrast strongly with Jones’s own account of what happened, but many of the same elements would be preserved. And most importantly, it wouldn’t tell us anything particularly meaningful about peer pressure, politics or, worse yet, “the human condition.” Nothing you could write about in a book report without looking like an idiot, anyway. Like all the best art.

But today, we’re talking about what Johnny Dawkins, Todd Strasser, and the team of Dennis Gansel and Peter Thorwarth all did with Ron Jones’s story to make it work for a wide audience in their three different adaptations, in respective order: The Wave the made-for-TV movie (1981), The Wave young adult novella (also 1981), and Die Welle (2008). These retellings of the original story drift further and further from what actually occurred in Ron Jones’s account, which is itself quite different from what actually happened in Cubberley High School. And for that reason, “The Third Wave” experiment and its subsequent retellings makes for an interesting case study in narrative drift more than any kind of lesson about fascism. So without further ado, let’s get into it.

I. The Wave, the made-for-TV movie

Ron Jones’s essay was picked up by the notorious left-wing sitcom tycoon Norman Lear, whose T.A.T. Communications Company produced it. It won a 1982 Emmy award for outstanding children’s program, a 1981 Peabody award, and a 1981 Young Artist award for Best Television Special under the category of Family Enjoyment. When I say that the Third Wave story constitutes a kind of metapolitical folklore, I am not using that term facetiously. It is genuinely impressive just how many people have seen this thing, and how eagerly they share the story through word of mouth. I first heard about it in college in the mid-00s when my supervisor at work told me about it with total credulity in his eyes, urging me to track it down and watch it. Even now, I’ll find that people I wouldn’t expect to have seen it indeed have. Love it or hate it, this thing made an impact.

Generally speaking, The Wave offers a more character-focused account of what happened, selecting a handful of students with their own characteristics and dilemmas to help anchor the story. For instance, in Ron Jones’s original essay, there’s a slow kid called Robert who gets really into his experiment and offers to be Jones’s bodyguard, even following him into the teacher’s lounge. In The Wave, some more attention is given to Robert. We also see more of Ron Jones (his name has been changed to Ben Ross) and catch a glimpse into his relationship with his wife, who isn’t mentioned once in the essay, but here is portrayed as another teacher in the school.

The inclusion of relatable characters is essential for any successful televised broadcast, and that’s why we have that here, but The Wave’s most effective moments occur in the directing itself. The film, albeit within its own hokey emotional universe, successfully portrays the students as mindless zombies, chanting out Mr. Ross’s fascist slogans with a glassy-eyed look on their faces as eerie music plays in the background. You can tell that there’s some influence from earlier horror films like Village of the Damned (1960), maybe some political horror/sci-fi films like The Stepford Wives (1975) or a few episodes of the Twilight Zone.

But I’m interested primarily in the changes that were made between Jones’s essay and what writer Johnny Dawkins decided to put into his script, and one of the most interesting things about his adaptation is that in an attempt to make the story more palatable (and perhaps more believable) for a mass audience, he comes closer to the truth of what happened on some key details than what Jones actually writes in his original account. All the more interesting because as far as I know, Jones did not offer Dawkins, Lear, or director Alexander Grasshof any consultation when they were working on it. Here are three major ways in which the adaptation actually comes closer to the real record of events:

1. The Wave features one girl (the protagonist) who opposes the whole experiment.

What the creators of The Wave understood was that in a visual narrative, there must be a character that the viewer can side with — someone whose perspective can be accompanied by the camera. And that person turns out to be Laurie, the girlfriend of the high school football player David, who thinks that The Wave will help his team win their upcoming game (all of the adaptations drop the “Third” from the movement’s name and just call it “The Wave”). Though she initially goes along with The Wave, Laurie eventually turns against it and writes editorials for the school newspaper The Gordon Grapevine about how it’s bad. She and David get into a big fight about it, David shoves her onto the ground, he realizes what a jerk he’s being, and then he takes her side. They then become the only two students who want to stop The Wave and help convince Mr. Ross to do something to stop it, which prompts him to create the bogus Wave rally.

Now, in the actual Third Wave experiment, there was one girl who pretty much singlehandedly opposed the Third Wave movement and created her own fake organization called The Breakers, plastering posters on its behalf all over the school and getting the principal to let her voice an anti-Third Wave message over the intercom. That would be Sherry Tousley, whom we’ve discussed plenty before. I don’t believe that the creators of the adaptation knew who Tousley was or that there was any resistance at all. The invention of Laurie and David seems to have been solely for narrative convenience. But it also can be understood as a psychological corrective to Jones’s account. Of course there’d be at least one student who opposes this fake social movement that clearly resembles Nazi Germany.

2. The Wave de-emphasizes the claim that the whole thing took place within just one week (and probably trashes it altogether).

In fact, The Wave discourages the viewer from keeping track of time at all. Characters never say what day it is, and the overall impression the viewer gets is that the experiment goes for longer than a week. There are two major hints indicating this:

First, after Mr. Ross has already introduced the concept of Strength Through Discipline, Strength Through Community, and Strength Through Action (they never get to “Strength Through Pride” for some reason), his wife tells him at home that her students are skipping her class just to attend his. This detail recalls what Jones said in his essay, and indeed what actually happened, but we never see any extra students. It just looks like Mr. Ross has had the same amount of people in the class the whole time. The most likely reason for this is because it would look terrible on video and undermine Jones’s claim that everyone remained very disciplined and orderly, even as they were crowded together and sitting on the floor. But because that detail is nonetheless preserved in the story, Mrs. Ross’s claim implies that multiple days have passed in which students were skipping her classes to attend his.

Additionally, when Laurie writes and publishes a student editorial attacking The Wave, one of The Wave’s members remarks that this is the second one she’s written! It’s hard enough to write and submit an editorial to a student newspaper, and then see it published all in one week. But twice? We never see any of this take place. There’s no sense of just how many days have passed, but the implication is that more than a week has gone by, which would be closer to the truth of what actually happened. I’m inclined to think that The Wave’s writer felt that just a week is a little unrealistic and decided to de-emphasize time altogether, allowing the viewer to make up her own mind about how long it took.

3. There’s a fight about The Wave.

In the last part of this series, I included a discussion about whether or not physical violence broke out about The Third Wave. And apparently, there was some violence. One fight apparently occurred with one or more non-members attacking members who were trying to proselytize too insistently (and it still isn’t altogether clear whether violence broke out or merely almost did). And another altercation occurred when some kids from the Car Club supposedly punched a student journalist in the stomach for trying to do a news story on The Third Wave (although this student never told anyone about it at the time). Now, in The Wave, we see the outcome of a fight being broken up in which a Wave member gets dragged away, his arm up in a “Wave” salute with a bizarre grin on his face and his eyes wide open, muttering “Strength through discipline! Strength through community! Strength through action!” to himself over and over. Clearly, a man possessed. Nothing is explained about what prompted this fight. Once more, the fight seems to be an imaginative detail that Johnny Dawkins threw into the story to spice it up, which just so happens to bear some faint resemblance to encounters that seem to have happened in real life. However, we really have no clear indication that any violence surrounding The Third Wave occurred because of the fanaticism of its members, or if it was just normal high school tussling, yet here, the student looks downright crazed and maniacal.

The rest, however, is mostly exaggerated.

Those three changes constitute attempts on the part of Dawkins to make the story more palatable for a television audience, and perhaps more believable from a psychological perspective, and they coincidentally come closer to the truth of what really took place. But the rest of the changes distort the story further, almost in a compensatory fashion. Without getting into excessive detail, here are some bullet points showing the changes, both major and minor, that make the story bear less resemblance to both the historical event and what Jones wrote of it.

Mr. Ross gives the students homework assignments and the students do them even better than before. As he puts it, “They do what I give them and more!” In reality, there was probably very little serious academic work involved.

There’s no mention of grades being a part of participating in The Wave itself, and little attention is given to what actually goes on in Mr. Ross’s classes past the first couple days.

Mr. Ross starts wearing a suit and tie starting on what seems to be the fourth day.

A guy in a convertible harasses Laurie and David on the street, angrily giving them a Wave salute before peeling off, suggesting that random people have been converted and empowered to act like dickheads.

There’s a Third Wave meeting after school that takes place at some point before the big rally, which Laurie refuses to attend. We never see this meeting or get a sense of how big it is.

All of the teachers and the principal start to have problems with The Wave experiment. In both real life and in Jones’s essay, they didn’t care at all. Also, sorry to get lost on this point, but if you’re going to adapt Jones’s essay, you really should include what’s possibly its best line: “The school cook asked what a Third Wave cookie looked like. I said chocolate chip of course.”

A student writes “ENEMY!” on Laurie’s locker after she has written her editorials attacking The Wave (she seems to be working on a third when this happens, since she’s leaving the school journalism room sometime in the evening).

Right after Laurie sees the “ENEMY!” message on her locker, a mysterious shadowy figure sees her from afar, lunges towards her, and chases her out of the school.

Laurie and David, as mentioned before, play a role in getting Mr. Ross to stop The Wave. Bizarrely, they just stroll up to his home to pay a visit in the evening. Maybe this sort of thing was common back in those days.

The big Wave rally is changed to 5:00 PM instead of mid-day when it really occurred. The students here are motivated enough to actually leave the school and come back for it.

The Wave rally has two televisions instead of one, and the auditorium is massive. The students aren’t dressed totally formally, but they are dressed somewhere between smart-casual and business-casual, suggesting that they’ve changed clothes just for the rally.

Mr. Ross’s speech is changed a bit at the end, with the stuff about how everyone’s going to keep the Wave rally a secret removed. He shows a bit of empathy and says that they’ve all learned a lesson together. This speech is a big improvement over the original one that Jones supposedly gave, whose ending really didn’t make much sense and was obviously wrong.

II. The Wave, the novel

Todd Strasser AKA “Morton Rhue” pumped out a novelized version of The Wave in 1981, the same year the TV-movie was made, and since then it has been required reading for school in many parts of the U.S., parts of Europe, and all over Germany, where Holocaust shame plays a central role in its national identity. What makes The Wave novel interesting is that Strasser shows no familiarity whatsoever with Ron Jones’s original essay in his work. Strasser spent much of the 80s and 90s writing hacky novelizations of films such as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Home Alone, Addams Family Values, and Free Willy 2: The Adventure Home. His novelization of The Wave was the first of these many adaptations, and serious research was evidently not a strong priority.

Instead, Strasser focuses on making the story more psychologically palatable for a young pre-adolescent audience, developing many of the loose ends and unexplored areas from the TV movie without concern for how close to the source events his own additions may be. So, for instance, since The Wave made-for-TV movie pays a decent amount of attention to Robert, the weirdo who gets a little too involved in The Wave, the novel pays even more attention to him, striving to present him as a fully-rounded character. It also gives more of a backstory on Ben Ross and his relationship with his wife Christy, even explaining that Ben has an obsessive personality and becomes fully absorbed into whatever passing fascination he’s preoccupied with at the time. Laurie, who seems only to be submitting guest editorials to the Gordon Grapevine school newspaper in the short film, is here depicted as an active part of their staff. David the football player is shown to be the quarterback, and his involvement with the team is greatly expanded upon. Additional characters are invented just to pad out the series of events that take place. And Strasser even restores a basic sense of chronology, making The Wave experiment take about a week and a half instead of one week. Again, we’re closer to reality here, but purely by accident.

However, there are some expansions to the text Strasser adds that deviate much further from what Ron Jones originally wrote. For instance, while the TV movie makes Laurie the lone opposition to The Wave (until David joins with her), in the novella Laurie gets nearly the whole staff of the Gravevine to turn against it, and they dedicate an issue entirely to why The Wave is bad. One of the writers, a wacky and zany guy named Alex Cooper, jokingly says that they should call themselves “The Ripple.” He also at one point says, “I pledge to fight the wave until the end. Give me liberty or give me acne!” This version contains the most overt propaganda in presenting journalists as a hindrance to burgeoning fascism.

There are a few additional changes worth mentioning. In this story, there are two Wave rallies, not one. The first one occurs on Friday, but it’s a pep rally for the football game, which becomes a de facto Wave rally. We never actually read about what happens in that rally, but we do read about the football game the next day. When Laurie tries to go up into the stands, she’s told that she has to give a Wave salute by a student who is acting as a guard. The implication here seems to be that most of the students have converted to The Wave, or at least they’ve all deferred to it. The next Wave rally, the one where the teacher reveals that Hitler would be their leader, occurs next week.

Here are a few more additions/changes in bullet points:

Mr. Ross not only has raised the hackles of his colleagues, but he actually has a meeting with the principal, who expressly states that he’s concerned things are getting out of hand.

The unexplained fight from the made-for-TV movie is given a backstory. It was between a football player named Deutsch who didn’t want to join The Wave and another player who wanted him to join. Apparently Deutsch was having tension with the rest of the team for a long time prior to The Wave. This explanation gives the situation an air of believability, but it also sucks the wind out of the notion that The Wave is possessing the students and turning them into deranged psychotics.

Even though nearly the whole football team decides to become Wave members, they still get their asses kicked at the home game.

Mr. Ross actually admits some wrongdoing in the final speech where he reveals that the leader of The Wave is Hitler. He also offers to have a discussion with Robert, so that he can help him maintain some of the confidence that The Wave gave him and be less of a weirdo. Of all the versions, this one shows the most concern for the class freak, who up to this point had been left hanging at the end, totally bereft of whatever hope he once had of being normal. The previous two accounts make it rather clear that “fascism” helped him quite a bit, and once it ended he was just meant to be a loser again.

These changes are all actually laudable from a realist perspective. Strasser’s dialogue is corny and the writing isn’t very good, but you can tell that he really wanted to make the story plausible. However, there’s a problem here. When you make something plausible, you also de-mythologize it, and The Wave story has to remain a kind of myth in order to achieve its intended purpose. Thus, Strasser has to walk a fine line, making sure that the reader knows that The Wave really is just like the Nazi party despite the fact that any attempt to soberly reason through it would point to an alternative conclusion.

This dilemma brings us to the most absurd addition Strasser makes: it contains blatant antisemitism. Sometime over the same weekend in which the football game occurs, Laurie learns that some Wave members beat up a Jew for some reason. They even reportedly called him a “dirty Jew,” making their intentions clear. This is really incredible. Some kids join a club that promotes discipline and community, and then they instantly think, “Wow, now I’m disciplined! Now I have a community! I know what to do next! I need to beat up some Jews!” This detail, along with the sheer power that The Wave instantly assumes over the rest of the school, was almost certainly thrown in as a compensation for the fact that Strasser gives more psychological credence to his characters than in any other version of the story. It also compensates for Strasser’s inability to express the story visually and acoustically, not having the ability to portray the students as mindless chanting zombies accompanied by ominous background music the way the short film did.

There are plenty of exaggerations in Strasser’s work — exaggerations on top of Jones’s already exaggerated story — but Strasser shows some attempt to temper them a bit. But these exaggerated parts only give us a taste of what’s later to come.

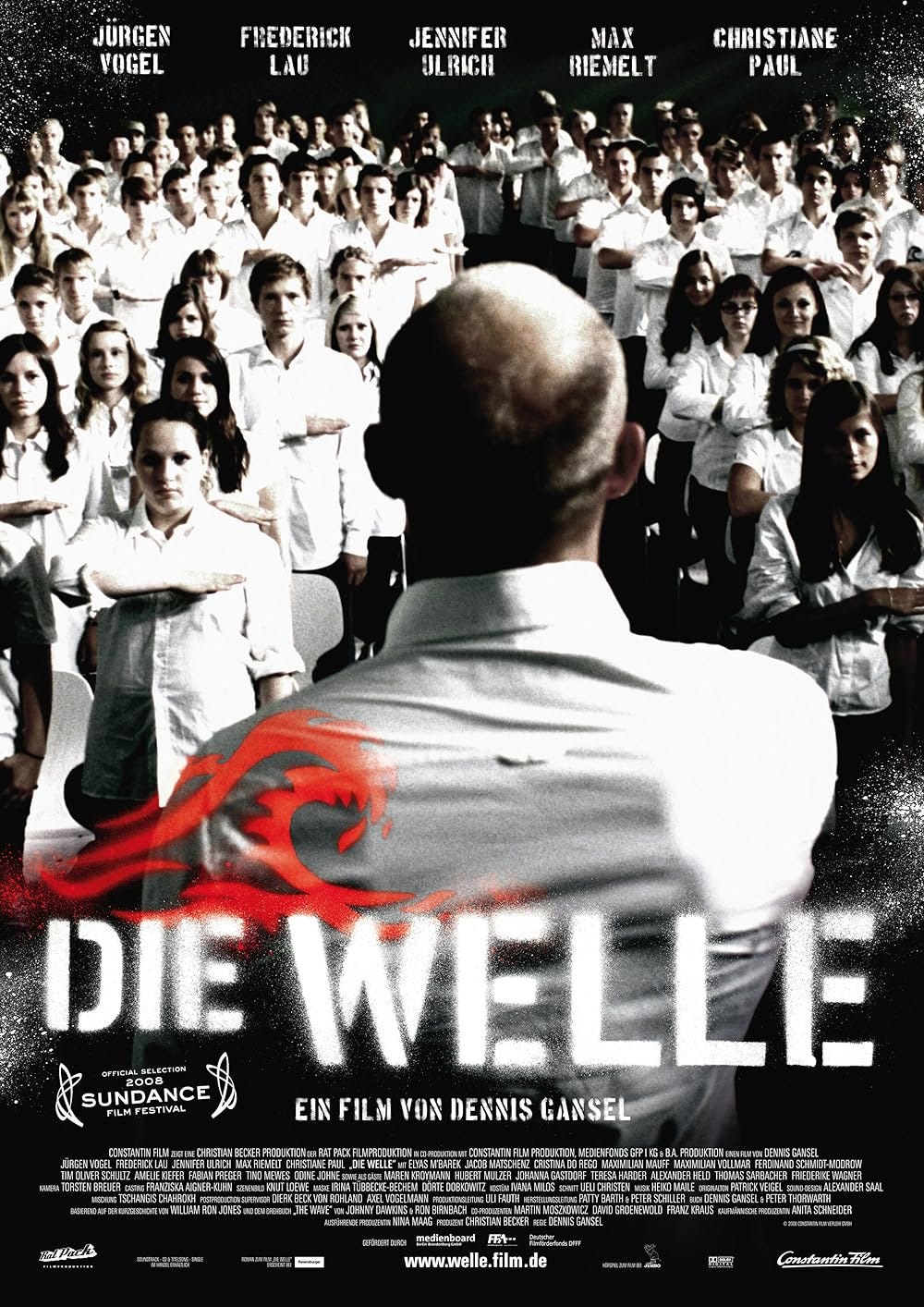

III. Die Welle, which is German for “The Wave”

We arrive at Die Welle, which has played a strong role in keeping the story of The Third Wave fresh in the public consciousness. By the time it was released in 2008, twenty-six years had gone by, and that’s a fairly long time. So when Dennis Gansel decided that he would adapt The Wave into a film, he understood he would need to make some adjustments, which meant that Die Welle would need to stray even further from reality than The Wave made-for-TV movie and novella. Gansel knew, however, how the original story went, and he consulted with Ron Jones in creating his movie. In fact, Ron Jones makes an uncredited “Easter egg” cameo in the film about halfway through it, and he attended the inaugural screening of the movie. Nonetheless, Gansel’s movie combines elements from all three accounts of what happened, while also making his movie more extreme and over-the-top in nearly every way. It is not a film that strives for historic accuracy.

In Die Welle, we find all the same basic characters from the made-for-TV movie, though they have different names and slightly different circumstances. Laurie becomes Karo, who is also a student journalist but also involved with a school play, an adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit, which they’re supposedly updating to contain a critique of capitalism. David becomes Marco, a water polo player. Robert becomes Tim, who is way more of a creepy weirdo than in any of the other versions. Mr. Ben Ross becomes Herr Rainer Wenger, a rock’n’roller who likes to teach in punk band t-shirts, and his wife is now named Anke. Although Gansel did show respect to Ron Jones’s original essay, it is much more of an adaptation of the Strasser novel than anything, though with nearly every detail exaggerated in some way.

Despite the film’s plot being aggressively melodramatic, the dialogue in Die Welle is better than anything we’ve seen so far. In the made-for-TV movie and novella, the creators apparently had a desire for the story to be realistic even while the dialogue is ridiculous. Here, the situation is exactly the reverse. The story is the most absurd of all versions, but the dialogue is reasonably realistic, at least given the subject matter. It is also has a far higher budget than any other Wave adaptation, which has encouraged people to take it seriously. Respected actors within German cinema played roles in it, and it has a more or less teen-friendly soundtrack. Moreover, the kids in this movie are all way more “adult” than in any other version. They get drunk, they smoke weed, they swear when outside school, and they do hip and happenin’ things like skateboard and spray-paint graffiti.

There are also, to be sure, occasional flashes of intelligent filmmaking here, though they don’t last long. Part of the reason for that may be due to Dennis Gansel’s co-writer, Peter Thorwarth, whom he hired to help him when he had gotten stuck plotting out the story. Thorwarth, at least in what I’ve seen from this interview, seems to be less ideological and more level-headed than Gansel (Thorwarth, to his credit, opposed the film’s ending, which we’ll discuss below). Nevertheless, these flashes of intelligence are always nullified almost instantly after they occur.

I’ll give an example. The film takes place in some sort of Gymnasium (German high school for smarter kids), and the classes are all meant to do a graded social studies project for one week based on assessing various political systems. The teacher in charge of “Anarchy” is a stuffed shirt who’s apparently making the students do a boring project. Wenger, who seems like a much more permissive and progressive teacher, is assigned to instruct the “Autocracy” group. So already, we have a nice incentive for the students to comply with Wenger’s instructions — their grades are on the line, and they like how he’s making a mandatory schoolwide project less boring. And we also have a motivated reason for students to switch out of the other class, like the Anarchy one, to attend his. However, this circumstance is not enough to explain much else of what goes on in the movie. Several times we find intelligent ideas like this thrown into the film, which Gansel then expects to do far too much heavy lifting.

I’ll jot down the plot along with a few observations in bullet points:

As mentioned above, Die Welle takes place only within one week. In the same way I suspect Ron Jones was influenced by the success of Phillip Zimbardo’s (equally fraudulent) Stanford Prison Experiment, I suspect Gansel was encouraged by the success of Das Experiment (2001), the German film about that experiment. Much like The Wave, Zimbardo’s story has also been used extensively in Germany as anti-Nazi education.

A slacker gets kicked out of The Wave project on day one, but then he later joins The Wave anyway outside of school despite having essentially failed the project.

Herr Wenger rearranges the seats on day two and imposes a class uniform, which he himself opts to wear. The students are later shown buying the uniform.

The next day, amazingly, every single student complies with his expectation but two: a hippie chick called Mona who switches classes, and Karo, who wears a red shirt to class and feels humiliated when the teacher and the rest of the class don’t take her seriously (this is probably the most intelligently executed scene in the film). Tim, the class weirdo, burns all of his other clothes after school.

After class on Wednesday, some of the students go skateboarding and decide to embrace Tim the weirdo as a fellow Wave member, defending him from bullies.

On the same day, the director of the school play, a Wave member, decides to kick Karo out of the play, acts a bit more like a leader, and the students cooperate better.

On the same day, Tim creates a Myspace page for The Wave with little guns on the front-page decoration.

On the same day, the skater kids along with Marco decide to spray-paint their “Wave” logo all over the town later at night, and they slap “Wave” stickers everywhere, in a sort of teenage youth culture version of Kristallnacht. Tim the weirdo decides to deface a building with a gigantic painted “Wave” logo after the other kids have gone home, running away from the cops.

On Thursday, the students create the “Wave” salute. I should mention that the students voted for the name “The Wave,” and they seem to be suggesting activities in a bottom-up fashion. In an earlier entry, I commented on how the bottom-up nature of The Third Wave experiment invalidates Ron Jones’s claim that the experiment resembled Nazi Germany. I still stand by this claim, though here, Herr Wenger is presented as being in full control over everything with full admiration from his students who seem to accept him as their leader, inside and outside of school. I should also point out that starting on day three, very little of what actually happens during his class is shown.

On the same day, Karo’s little brother, who has also joined The Wave tells a chubby kid that he can’t enter a school building without giving a Wave salute. This prompts Karo to urge Wenger to stop the experiment in his office. Wenger refuses and tells her she should change classes (they’re already four days into what’s meant to be a one-week project!)

On the same day, Karo talks to her journalism club (or something), they decide that they can’t put out an anti-Wave issue of their paper in one day, and so they agree to send out anti-Wave emails to everyone.

On the same day, the principal talks to Wenger and tells him that he has her full support (this is more similar to Ron Jones’s essay, and what actually happened)

On the same day, Tim and the skaters are confronted by some ugly punk rockers in leather jackets, who challenge them to a fight. Tim the weirdo pulls a gun out on them and they walk away looking mortified. Tim assures everyone it’s only filled with blanks.

On the same day, there’s a gigantic party lakeside where everyone gets drunk, and Marco makes out with another girl, cheating on Karo.

On the same day, Tim the weirdo goes to Wenger’s house, tells him he wants to be his bodyguard, eats dinner with Wenger and his wife, and then sleeps on the ground outside their house unbeknownst to them.

Oh, and on the same day, Karo realizes she can’t send the emails out from the journalism room for some reason (maybe Tim somehow tampered with the computers or something, I couldn’t quite follow the logic there).

On Friday, Herr Wenger yells at the students about Tim’s gigantic spray-painted graffiti sign on the building, which has shown up in the newspapers. He then has the class write about their experiences with The Wave the whole time.

On the same day, Marco has his big water polo game, Karo and Mona the hippie chick distribute anti-Wave flyers that they’ve printed out during the game, and this leads to a gigantic fistfight with a bunch of people.

On the same day, Marco gets into an argument with Karo and slaps her hard in the face, causing her to shed blood.

On the same day, Wenger gets into a big fight with his wife about The Wave, and she leaves the house, deciding to sleep elsewhere. Marco then shows up at Wenger’s house, asks him to stop the experiment, and Wenger refuses.

On the same day, shortly afterwards, Wenger changes his mind and sends a mass text message to all the students telling them to attend a Wave rally on Saturday at noon. For some reason, the students are not partying at all like they did on Thursday.

On Saturday, what looks like over a hundred students show up all in white shirts for some reason, and Wenger reveals to them that it was all a trick, Tim the weirdo loses his mind, shoots one of the students, and then kills himself. Wenger is arrested by the police while all the students cry and feel miserable.

Now, listen. I’m not sure if you noticed, but that’s a lot of shit crammed into just a few days, especially Thursday and Friday. No students anywhere in the world lead such fascinating, event-filled lives. Moreover, the very end is just absurd — it effectively makes the whole movie into a study on Tim rather than a statement about fascism. After all, Tim is the one who painted the gigantic logo on the building and got the attention of the authorities, Tim is the one who made the Myspace page with the guns on it, Tim is the one who somehow blocked Karo from sending out emails (I think?), which prompted her to distribute flyers, which then led to a fight, Tim is the one who slept in Wenger’s front yard which caused his wife to recognize a serious problem, leading to the break-up of their marriage, and then on top of all that, Tim turns out to commit a murder-suicide. And this is to say nothing of his other ridiculous behavior that I didn’t bother to address. They even make him a weed dealer in the beginning of the film!

But the ending is also a great example of how the film tends to step on its own toes right as soon as does something smart. If we ignore the improbable number of students who decided to show up to school on a Saturday, the actual rally itself is intelligently executed up until the end. Instead of showing a video of Hitler and saying, “There’s your leader!” Wenger gives a rousing political speech about how Germany should no longer take crap from other countries in Europe, the students cheer, and he gets them to drag Marco up to the front because of his recent change of heart. Only then does Wenger reveal that it was a trick and the students have become like the Nazis, because they were ready to hurt their friend. Again, this is silly stuff, but it was at least better-thought-out than what’s in The Wave short film or the Strasser adaptation. At least, that is, until the school shooting occurs and we’re fully back in wacky-land.

There’s a certain irony that underlies this film. Although the ostensible purpose of Die Welle is to remind the Germans that they’re an inherently guilty people, always a mere stone’s throw away from becoming Nazis and having another Holocaust, the sheer exaggeration with which everything is expressed still, in its own strange manner, suggests a kind of German exceptionalism. It might be self-loathing, but it’s definitely there. In every recounting of The (Third) Wave up to this point, no one actually died, and the violence that did break out was unfortunate but not terribly serious. In this film, however, property is destroyed, authorities get involved, a guy draws blood from his girlfriend, and people certainly die. In the TV special and novella, the creators realized that making the whole film take place within one week was just a little too ridiculous, so they made it take a bit longer. In this movie, the story goes back to taking place within just one week. That’s German efficiency, for you. And in the other versions, when Laurie and David get into a fight, there’s a bit of drama, but it’s resolvable. Here, Marco cheats on Karo, slaps her silly, and yet they wind up somewhat lamely hugging each other in the end. Whenever an opportunity arises to adapt a story element from a previous version and “take it to the extreme,” Gansel pounces, always to the film’s detriment. Part of this is surely because he wanted to get the attention of a relatively desensitized young adult audience. But there’s also a sublimated message being communicated, which goes something like,

Hey, we Germans are extreme! We’re a ticking time bomb waiting to explode! And you know, if we had a Third Wave experiment done at one of our Gymnasien, it wouldn’t be anything like that pussy-ass Third Wave experiment the Americans did. Why, if we did it, our movement would grow so strong that we could potentially take over all of Germany within a month!

As this post stated at the outset, every adaptation represents both an homage and a critique. Die Welle’s unstated critique of the TV special and Strasser’s novella is that their message’s implied universality is false. It isn’t enough to say that there’s a hidden Nazi lurking in everyone all around the world. That’s just some liberal pablum. No, the Nazis are really lurking in the Germans.

Most of all inside the Germans.

But because of this over-the-top version of The Wave, a whole new generation of German youths essentially have had the story revitalized in their minds, leading them to treat the hysteria of the 2008 film as an interpretive emotional lens through which they might understand the original 1967 event, which as I’ve shown was little more than an amusing but ultimately unremarkable situation. The reason that the “Third Wave” story has been itself like a wave is because its legend has only picked up more and more emotional momentum over time, transferring from version to version, person to person. And yet, right alongside its mythologization, more and more evidence has been found giving us every reason to see it as the meaninglessness that it really was.

Next week, I’ll conclude this series and discuss some principles of modern metapolitical folklore.